|

| Topics on Continuous Training |

Pediatric Surgery Service. Niño Jesús University Children’s Hospital. Madrid

| Abstract

Undescended testes (UDT) and acute scrotum comprise the main benign pathologies of the testicle. Empty scrotum and acute pain associated with scrotal swelling are the characteristic signs in scrotal examination, respectively. Furthermore, distinction between palpable and non-palpable testis is crucial in the management of patients with UDT. Cryptorchidism as the commonest male genital malformation, is under the influence of genetic factors, sometimes in association with other syndromic conditions, or others as low birth weight or prematurity, which affect the genesis and testicular descent in both transabdominal and inguinoscrotal phases. Orchidopexy is the treatment of choice that consists on the descent and fixation of the testicle in the scrotum, in its physiological and palpable location. It must be undergone within the first twelve months in order to avoid fertility damages and the development of testicular cancer in the future. Acute scrotum is mainly caused by Morgagni torsion, epididymitis and testicular torsion, situations that require an early assessment so as to rule out the latter situation. The diagnosis is based on clinical and physical examination. Doppler-ultrasound being the preferred imaging test, should never delay the early and accurate diagnosis in patients with a high suspicion of testicular torsion. Surgical exploration of the testis is the treatment of choice in patients with testicular torsion, associated with orchidopexy if testicular viability is confirmed. Epididymitis and most cases of testicular appendix torsion resolve with medical treatment. |

| Resumen

Las alteraciones del descenso testicular y el escroto agudo constituyen las principales patologías benignas del testículo. Se manifiestan por alteraciones en la exploración escrotal, como: escroto vacío en el caso de la criptorquidia, y con dolor y signos inflamatorios de corta evolución, en las situaciones de escroto agudo. Además, la clasificación en función de la palpación o no del testículo, es determinante en el diagnóstico y tratamiento de los pacientes con maldescenso testicular (MDT). El MDT es la malformación genital más frecuente en los varones, en la que se han demostrado factores genéticos, a veces, en asociación a otros síndromes, u otros, como la prematuridad o el bajo peso al nacer, influyentes en el descenso testicular. El tratamiento de elección es la orquidopexia, con el objetivo de posicionarlo en su localización normal y palpable en el escroto. Debe realizarse de forma precoz, preferiblemente al año de edad, para evitar defectos sobre la fertilidad o el desarrollo de cáncer testicular en el futuro. El escroto agudo, cuyas causas más frecuentes son: la torsión de hidátide testicular (Morgagni), la epididimitis y la torsión testicular, requieren una valoración precoz que descarte esta última situación. El diagnóstico se basa en la historia clínica y la exploración física. La ecografía-doppler, prueba complementaria de elección, se plantea siempre que no suponga un retraso en el diagnóstico de los pacientes con alta sospecha de torsión testicular. La exploración quirúrgica del testículo es el tratamiento indicado en la torsión testicular, asociado a orquidopexia si se confirma viabilidad testicular. La orqui-epididimitis y la mayoría de los casos de torsión de hidátide testicular se resuelven con tratamiento médico. |

Key words: Undescended testis; Acute scrotum; Scrotal; Testicular torsion; Pediatric.

Palabras clave: Maldescenso testicular; Escroto agudo; Escrotal; Torsión testicular; Pediátrico.

Pediatr Integral 2024; XXVIII (6): 354 – 370

OBJECTIVES

• To recognize the main aspects of the diagnosis of undescended testes (UDT) and other benign testicular-scrotal pathologies. To identify warning signs for the primary care pediatrician.

• To update the algorithm of action in patients with UDT.

• To be aware of the indications for referral and treatment in benign testicular pathologies.

• To present the possible complications and consequences of UDT and benign testicular pathology.

Cryptorchidism and scrotal pathology

Introduction

This article addresses the most common benign testicular pathologies, which share the common feature of abnormalities in scrotal examination. For a better understanding and based on their origin and most common clinical course, they will be dealt according to the following classification:

1. Cryptorchidism or testicular maldescent: alterations in testicular development and descent, of malformative origin.

2. Acute scrotum: acquired testicular disorders with an acute clinical course.

3. Other scrotal pathologies: of acquired or malformative origin and variable clinical course.

Given the importance of the potential impact on testicular viability in many of these situations, proper diagnosis and follow-up of testicular descent disorders or other pathologies, such as varicocele, as well as recognition of warning signs in cases of acute scrotum, are essential and are the main objective of this article.

Testicular developmental and descent disorders

Testicular descent into the scrotum may continue into the postnatal period, up to 6 months or 1 year of age. Undescended testicles are the most common genital malformation in newborn males.

Although cryptorchidism is often used in general terms to refer to the absence of a testicle in the scrotum or even a non-palpable testicle, it is preferable to use the term maldescended testicle (MDT) or undescended testicle. By doing so, all the alterations caused by a disorder in testicular development and/or descent are more appropriately included, which give rise to examinations of both palpable and non-palpable testicles.

The descent of the testicle from the abdominal cavity may be completed spontaneously during the first months of life, during the 6 months in full-term infants (absence of testicular descent is observed in 1%, at 1 year) and up to the first year in premature newborns (NBs). Thus, undescended testicles constitute the most frequent congenital genital malformation in newborn males, with variable prevalence according to gestational age: 1-5% in full-term NBs and 30-40% in preterm NBs.

It is bilateral in 30% of patients. In these cases of bilaterality with non-palpable testicles or in those cases of MDT in which some other suspicious sign of alteration in the development of sexual differentiation is detected (hypospadias, bifid scrotum, etc.), an endocrinological evaluation and genetic study should be requested.

Despite spontaneous descent, in many cases, clinical follow-up for several years during childhood is advisable, given the possibility of acquired testicular “reascension” (40%)(1,2).

Classification

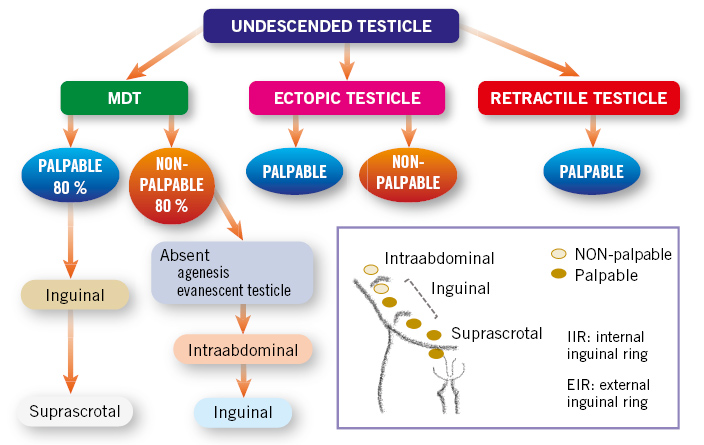

This is based on the etiopathogenesis of MDT, and on the physical examination depending on the location of the testicle and whether we are dealing with a situation of palpable or non-palpable testicles(3-5) (Fig. 1):

Figure 1. Classification of undescended testicles based on their pathogenesis and location. The situation of a palpable or non-palpable testicle is indicated according to the testicular position. MDT: undescended testicle.

• Congenital testicular maldescent: the testicle is located outside the scrotal sac, at any point along the normal path of descent. They may be: palpable (80%), when located external to the internal inguinal orifice; or non-palpable (20%), located deep to the internal inguinal orifice or intra-abdominally.

On physical examination, palpable testicles may occasionally be pulled into the scrotum, but they immediately “reascend”, which differentiates them from retractile testicles.

• Ectopic testicle: the testicle is located outside the scrotum at an extra-abdominal level, in an “aberrant” position, different from the normal descent path. It is most frequently located in the region of the superficial inguinal ring or at the pubic level. Other, less frequent, possibilities are: the femoral or perineal region. Usually, they are palpable testicles and do not descend spontaneously, so they require surgical treatment.

• Absent testicle, due to two possible pathogenic mechanisms: 1) testicular agenesis; or 2) testicular atrophy secondary to intrauterine testicular torsion, a situation known as “evanescent testicle”(5).

• Retractile testicle: it is caused by an exaggerated cremasteric reflex. They are always palpable in the inguinal region or at high points in the scrotum, and they are easily lowered into the scrotum with manual traction, remaining in the scrotum for a while. It is considered a physiological situation, which does not require treatment, since the testicle has completed its descent to its normal position in the scrotum. However, they should be followed up in consultation with periodic examinations, since up to a third of cases may have a subsequent ascent.

• Acquired undescended testicle: the testicle is located in the scrotum during the first year of life, but later rises due to the lack of growth of the spermatic cord, which remains short and retracts the testicle. They can be considered to be true retractile testicles. They are often detected between 5-10 years of age.

Pathogenesis and embryological aspects(3,6-9)

In the etiopathogenesis of cryptorchidism, the main causes described are: genetic factors, including those affecting the Y chromosome or the INSL-3 gene, prematurity or low birth weight.

Formation of the testicle

The undifferentiated gonadal ridge develops into the testicular gonad from the 6th-7th week of gestation (WoG), influenced by the action of the transcription factor SRY (sex-determining region Y) and subsequently by other molecules (WT1, SF1, SOX9, FGF9), which in turn trigger the development of the Sertoli and Leydig cells of the testis. The former, by secreting anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), trigger regression of the Müllerian ducts and exert a trophic action on sperm. On the other hand, the Leydig cells, by releasing testosterone, induce the development of the Wolffian ducts (which give rise to the vas deferens and seminal vesicles) and, through its metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the development of the male external genitalia. Leydig cells also release insulin-like factor 3 (INSL3), which produces the growth of the gubernaculum testis, which will accompany the descent of the testicle into the scrotum.

Testicular descent into the scrotum

The testicle descends from the retroperitoneum to the scrotum in two phases, which can end physiologically up to 3-6 months after birth:

1. Transabdominal phase: controlled by the insulin-like hormone 3 (INSL3), produced by Leydig cells, which stimulates the growth of the gubernaculum for its subsequent migration in a caudal direction. In this phase, the testicle slides through the abdominal cavity attached to the gubernaculum until it is located in the internal inguinal orifice, towards the 15 WoG.

2. Inguinoscrotal phase, more complex and influenced by the action of androgens, in which the gubernaculum must grow and migrate 4-5 cm from the inguinal region to the scrotum, thus guiding the movement of the testicle from the entrance into the inguinal canal to the scrotum. This is the stage usually affected in cases of MDT, which explains why the most frequent location of undescended testicles is the inguinal region. It ends around 35 weeks of age and can last until the first months of postnatal life, helped by the transient rise in gonadotropins in the first 6 months after birth, which causes stimulation of Leydig cells and, therefore, an increase in testosterone levels.

Genetic causes

• Chromosomal alterations affecting the Y chromosome: Klinefelter syndrome or other structural alterations of the Y chromosome.

• Genetically based syndromes with involvement of other chromosomes: Noonan syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome (alteration in chromosome 15) or Wiedemann-Beckwith syndrome (alterations in chromosome 11).

• Alterations in AMH secretion secondary to dysfunctions in the activation of the transcription factor SRY, and others such as: WT1, SF1, SOX9, FGF9 and DAX1. They produce abnormalities in the differentiation of the internal genitalia, in the secretion of testosterone and in its transformation to dihydrotestosterone, affecting the development of the external genitalia and testicular descent.

• Mutations in INSL-3 gene (“insulin-like factor 3”) and its receptor LGR8, involved in the masculinization of the gubernaculum testis.

Prematurity

Prematurity or low birth weight influence the appearance of cryptorchidism. Prematurity is a favorable situation for MDT, due to the descent of the testicle during the third trimester of pregnancy, with the possibility of being completed during the first 3-6 months after birth.

Environmental factors

Research should be conducted on exposure to maternal factors such as hypertension, tobacco or the use of analgesics during pregnancy. Likewise, contact with chemical substances such as pesticides, phylates and thalates (constituents in some plastics), with estrogenic properties, could affect testicular descent by acting as endocrine disruptors, interfering with the synthesis or action of androgens.

Testicular atrophy

Due to ischemic accident during pregnancy: intrauterine torsion.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of MDT is based on clinical data and physical examination, which is complemented by ultrasound in cases of non-palpable testicles, or in those in which alterations in sexual differentiation are suspected.

Medical history

It should include family and/or personal history of cryptorchidism or other alterations in male genital development. Obstetric history: gestational age, birth weight, intake or contact with anti-androgenic drugs during pregnancy. Request information about the moment when the MDT was noted; as well as whether the testicle was noted in the scrotum on any occasion or whether the alteration is reported as unilateral or bilateral.

Physical examination

The examination should be performed in a warm and quiet environment. The patient should be supine with the legs flexed and abducted. In case of doubt, the patient can be examined in a squatting position or with the patient sitting with the legs crossed (Taylor examination). The inguinoscrotal examination is performed by bimanual palpation in search of the location of the testicle. The fingers are placed at the level of the internal inguinal orifice and are slid along the inguinal canal to the scrotum. The following should be assessed: whether the testicle is palpable or not palpable and, if the former, its location, as well as its size, consistency and mobility. Also, whether the involvement is unilateral or bilateral. During the inspection of the scrotum, the morphology of the scrotum should be assessed: scrotal asymmetry or hypoplasia. In unilateral cases, the finding of an increase in scrotal size on the side where the testicle is palpable should raise suspicion of compensatory scrotal hypertrophy and a history of intrauterine testicular atrophy as the cause of the non-palpable testicle on the contralateral side.

The presence of other alterations in male genital development (hypospadias, scrotal alterations, penile implantation, etc.) that could suggest the existence of alterations in sexual differentiation should be ruled out(3,7).

Hormonal and genetic study

In the presence of bilateral cryptorchidism, alterations in external genitalia or non-palpable testicles and suspicion of intra-abdominal testicles, the diagnosis must be completed with the request of karyotype and hormonal function tests (gonadotropins, testosterone and its metabolites, inhibin and AMH), which will be assessed during follow-up by Endocrinology specialists(4).

Imaging tests

In the case of palpable testicles, the diagnosis of MDT is clinical and no additional diagnostic test is necessary. Abdominal and inguinal ultrasound is indicated for cases of non-palpable testicles. This detects the existence of testicles in an inguinoscrotal location in most cases, with sensitivity and specificity close to 100%. However, in patients with intra-abdominal testicles, sensitivity and specificity drop to 50% and 75%, respectively, so the non-detection of a testicle by ultrasound does not rule out the existence of an intra-abdominal testicle(4). In any case, although ultrasound can help in choosing the approach (one can choose to start surgical exploration via the inguinal route in cases where the testicle is detected ultrasound-wise in the inguinal canal), it is not essential in patients with a non-palpable testicle, since surgical exploration and orchidopexy will always be indicated in these cases, in cases where the existence of a viable testicle is confirmed.

Abdominal ultrasound is recommended in patients with cryptorchidism in whom sexual development disorders are suspected, in the search for intra-abdominal testicles, malformations of internal genitalia or even the presence of abdominal tumors of a hormonal secreting nature, causing alterations in sexual development. In case of doubt, the radiological study should be completed by performing an abdominopelvic MRI to confirm or rule out these abnormalities.

In cases where ultrasound cannot confirm the presence of a testicle and the existence of intra-abdominal cryptorchidism is suspected, abdominal laparoscopic examination is indicated in search of an intra-abdominal testicle or even testicular atrophy or agenesis(3-5,8,9).

Treatment(3-7,9,10)

Age and the distinction between palpable and non-palpable testicles are the key aspects to consider in the treatment of MDT. When MDT is diagnosed, the treatment of choice is early orchidopexy: lowering and fixing the testicles to the scrotum, preferably before one year of age.

The objective of treatment of undescended testicles is to place the testicle in its normal scrotal position, allowing it to grow at the optimal temperature (33ºC) for the correct development and differentiation of gonadal stem cells, thus minimizing the risk of the appearance of sequelae and complications related to infertility or testicular cancer in the future. Likewise, the normal positioning of the testicle in the scrotum allows for its examination and the early detection of acute scrotal conditions or the presence of testicular tumors.

The treatment indicated for patients with MDT is surgical. The objective is to locate the testicle, lower it and fix it in the scrotum (orchidopexy), or to remove testicular remains in cases of testicular atrophy.

The fundamental aspects to take into account are: the age indicated for surgical intervention, the distinction between palpable and non-palpable testes in terms of the choice of surgical techniques to be performed, and the monitoring of retractile testicles, until being able to definitively rule out acquired testicular ascent, which requires surgical treatment.

Age(4,9,11)

Surgical treatment should be performed around one year of age, from 6 months onwards and not before, due to the possibility of spontaneous descent until then. Early orchidopexy is recommended: up to 12 months or, at the latest, 18 months of age, which is the time limit considered for the recovery (“catch up”) of a fertility potentially damaged by the changes in testicular germ cells and the depletion of Leydig cells, described above. This indication is especially established in cases of bilateral cryptorchidism, in non-palpable testicles, or in palpable ones in which the testicle is located at a “high” level in the proximal inguinal region, at the level of the internal inguinal orifice. This consensus regarding the indication of early orchidopexy is based on the results published in patients with MDT operated on at one year of age, in which greater testicular volume growth and better spermatogenesis indices have been demonstrated in testicular histological studies. Also, hormonal studies have revealed higher levels of inhibin B and lower levels of FSH in patients operated on before 2 years of age, compared to those operated on at later ages.

Palpable testicles

The technique of choice is orchiolysis and funiculolysis (section of the gubernaculum testis and dissection of the cremaster muscle and elements of the spermatic cord), lowering the testicle into the scrotum and fixing it there: a procedure known as orchidopexy(5). The aim of orchidopexy is to release the testicle from its attachments to the pubis, locate a patent peritoneal vaginal canal (ppvc) for its ligation and section, if present, and elongate the spermatic cord to facilitate testicular descent. This first step allows testicular descent for subsequent orchidopexy.

This surgical procedure can be performed either via the inguinal or scrotal route (Bianchi technique), reserving the latter approach for the testicles located caudally to the external inguinal orifice, close to the scrotum.

In patients with bilateral cryptorchidism, a two-stage procedure may be considered, separate for each side, especially in those in which the testicles are located high in the inguinal canal, and a more complex procedure is anticipated, with a higher risk of perioperative complications in terms of bleeding or injury to the tissues of the spermatic cord or the testicle itself. Also, in those situations in which the testicle is located high and/or has a short spermatic cord, it is necessary to perform the orchidopexy in two stages: initially leaving the testicle at some point in the inguinal canal, for its subsequent lowering months later, to the scrotum, if possible.

Orchiopexy does not require prophylactic antibiotic treatment and is usually performed as a major outpatient surgery procedure in the absence of a history or clinical data that require hospital admission.

The “key” points of the inguinal orchidopexy technique are described below (Fig. 2):

Figure 2. Orchiopexy, inguinal approach. A. Gubernaculum testis fixed to the pubic region (arrowhead). B, D. Patent peritoneovaginal duct ppvd (asterisk) next to the spermatic cord elements. In figure D, the ppvd has been opened for dissection and ligation at the time of funiculolysis. The epididymis (e) is dissociated from the testis. C. Orchiolysis and funiculolysis completed. The small size of the spermatic cord elements (arrow), which are hypoplastic, is shown. Epididymo-testicular dissociation (e). E. Orchiopexy by suturing the testis to the scrotal sac. Inguinal incision made for orchiolysis and funiculolysis in the previous step (arrow). Source: property of the author.

• Inguinal skin incision and entry into the inguinal canal by opening it, trying to locate the ilioinguinal nerve, which runs close to the spermatic cord, for its preservation(*).

(*) In the case of the Bianchi technique, the steps described above are performed through a single scrotal incision. The choice of inguinal or scrotal approach, in cases of palpable testicles distal to the external inguinal ring, depends on the surgeon’s experience and preferences, as there are no explicit indications for one approach or the other in these cases, since the results and complications of orchidopexy are comparable.

• Orchiolysis: mobilization of the testicle by section of the gubernaculum, and funiculolysis: dissection of the cremaster muscle and the elements of the spermatic cord. This allows: 1) the location of a ppvc, if present, for its section and ligation at its base, close to the internal inguinal ring; and 2) reduction of tension in the spermatic cord for lowering the testicle in a scrotal direction.

This step is the most delicate due to the risk of damage to the spermatic vessels or the vas deferens during their dissection.

At this stage, the testicle should be inspected in relation to its exact location, size, appearance (dissociation) epididymo-testicular function, status of the spermatic vessels and the vas deferens, or signs of atrophy). Likewise, removal of the testicular appendages or the epididymis will be performed, if confirmed.

• Skin incision in the scrotum and creation of a scrotal sac at the sub-darthros level, for the accommodation of the testicle.

• Suture of both wounds: inguinal and scrotal.

Non-palpable testicles

The aim of treatment is to confirm or rule out the existence of a testicle and to examine it if it is present, to perform orchidopexy if it is in good condition or to remove it in the case of evident atrophy.

In all cases, inguinoscrotal exploration under anesthesia is always necessary as a first measure, since this can allow palpation of the testicle and its location in the inguinal canal in patients who were diagnosed with non-palpable testicles during the examination in the office(12). In those situations in which the presence of a testicle in the inguinal region is confirmed or the cord is palpable, the surgical intervention continues via the inguinal route. If, on the other hand, this is not possible, the option is preferably to perform a laparoscopic examination to confirm or rule out the presence of a testicle and/or elements of the spermatic cord in the abdominal cavity or at the entrance to the inguinal canal. It would also be possible to continue the search for the non-palpable cord and testicle via the inguinal route, by means of dissection towards the peritoneum through the internal inguinal ring, proceeding to lower the testicle via the inguinal route, in the event of finding the testicle, or to perform a laparoscopic examination when it is not located via the inguinal route.

Laparoscopic examination (Fig. 3)

Figure 3. Exploratory laparoscopy in patients with cryptorchidism and nonpalpable testicles. A. Intra-abdominal testicle. B. Laparoscopic image at the level of the internal ring. Hypoplastic spermatic vessels with a “blind” end can be seen (arrows). The vas deferens is also amputated at this level (arrowheads). Source: property of the author.

It is considered the technique of choice in the treatment of non-palpable testicles. Laparoscopy allows confirmation of the presence or absence of intra-abdominal testicles and their appearance (non-visualization by ultrasound does not rule out their presence), inguinal rings, persistence of the vaginal process, and examination of the elements of the spermatic cord: vas deferens and spermatic vessels.

In most patients (80%), this approach confirms the entry of the spermatic cord elements through the internal inguinal ring or the presence of a viable testicle in the intra-abdominal cavity; other less frequent possibilities are: the location of an intra-abdominal atrophic testicle (10%) or the “amputation” of the spermatic vessels or the vas deferens in the retroperitoneum, without the presence of a testicle (10%).

In patients in whom laparoscopic examination shows elements of the spermatic cord entering the inguinal canal, the intervention will continue via the inguinal route, to search for the testicle and fix it to the scrotal sac if it is viable, or to proceed to remove the testicular remains if it is not.

In those cases where the presence of a viable intra-abdominal testicle is observed, the procedure of testicular descent and pexy in the scrotum can be continued, either laparoscopically or inguinally, depending on the findings:

• In those situations where the spermatic cord is short, making it impossible for the testicle to descend into the scrotum, a two-stage sequential procedure will be indicated, according to the Stephens-Fowler technique. Initially, the spermatic vessels are sectioned, leaving the vascular supply to the testicle through the vas deferens artery. In a second phase (months later) in which the development of collateral vessels is anticipated, the testicular descent towards the scrotum is carried out. The development of these elongated collateral vessels facilitates the mobilization and descent of the testicle towards the scrotum, with an approximate success rate of 85%.

• In rare cases where a long spermatic cord is observed, the testicular descent into the inguinal canal can be performed laparoscopically in a single stage, to complete the inguinal orchidopexy.

• Finally, in cases where there is presence of an atrophic intra-abdominal testicle, laparoscopic orchiectomy will be performed, ending the procedure at this point.

As has been discussed in the treatment of palpable testicles, in MDT with bilateral non-palpable testicles, and for any of the chosen techniques, a two-stage orchidopexy is recommended, delaying testicular descent on the second side to allow time to evaluate the results of the first orchidopexy. Thus, in those situations in which testicular atrophy of the descended testicle has occurred during the evolution, there is the possibility of performing a less aggressive surgical intervention on the contralateral side, with less dissection of the spermatic cord and a lower risk of testicular atrophy. It is even possible to consider leaving the testicle in a palpable location, more proximal to the scrotum, to minimize testicular damage.

General considerations in the surgical treatment of MDT(3-5,7,9)

• It is important to remember that testicular biopsy is not a routine procedure indicated during the techniques of orchidopexy, being recommended only in special situations, such as in cases of ambiguous genitalia, chromosomal alterations or as part of other studies in patients with endocrine pathologies.

• During the postoperative period, physical effort and sports that cause microtraumas in the scrotal area should be avoided, for approximately one month.

• The postoperative follow-up will be carried out at variable intervals (starting every 3-6 months during the first year), assessing the position of the testicle and its growth at each check-up, until puberty.

• Local inflammatory changes are common after orchidopexy, which may occur in the scrotum or even in the inguinal region. Other less common mild complications include infection, hematoma or dehiscence of the surgical wound. Other less common complications include testicular “reascension”, which requires surgical treatment, or injury to the vas deferens.

• Testicular atrophy is the most severe complication of surgical treatment, with variable rates depending on the technique: 2% in inguinal orchidopexy, 8% in the classic two-stage Stephens-Fowler technique, or 28% in the latter when performed in a single stage. It occurs due to damage to the spermatic vessels or severe post-surgical inflammatory changes on the spermatic cord or testicular parenchyma.

Hormonal treatment

Although it is not indicated to induce testicular descent(3,7,8,12,13), some authors defend its indication as an associated treatment to orchidopexy, due to the possibility of improving future fertility(14). Thus, in the European guidelines for pediatric urology(4), hormonal treatment with GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) is contemplated in patients with bilateral cryptorchidism, according to a level of evidence 4, since conclusive results in this regard have not been demonstrated. On the contrary, treatment with hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) is rejected, due to the side effects on spermatogenesis by producing apoptosis in germ cells, inflammatory changes and a decrease in testicular volume(3).

Retractile testicles and acquired testicular ascent

Retractile testicles are those that rise out of the scrotum as a result of the physiological contraction of the cremaster muscle and therefore do not require treatment. During examination, they are easily lowered into the scrotum with manual traction, remaining in the scrotal position during the physical examination. It is very important to differentiate them from congenital maldescended testicles or those that re-ascend over time due to a shortening of the spermatic cord (also called true retractile testicles), both situations requiring surgical treatment.

The acquired ascended testicle can occur from 6 months of age, coinciding with the decrease in androgen levels that have kept the cremaster muscle more relaxed and the growth of the scrotal dartos muscle, during the period known as “minipuberty”, between 2 and 6 months of age. From this moment on, the decrease in testosterone levels thins both structures, favoring the “pushing” of the testicle out of the scrotum. Also, the retraction of the testicle can be due to the permanent fibrosis of a previous ppvc which, in turn, shortens the elements of the spermatic cord(9).

Differentiating the cause of this testicular retraction: 1) due to muscular contraction in the case of retractile testicles; or 2) due to tissue shortening of the spermatic cord, in the case of true retractile testicles, is crucial. In the first case, we are faced with a physiological situation; and in the second, we are faced with a situation of acquired testicular maldescent, which will require the performance of orchidopexy, usually between 5 and 10 years of age. For this reason, these patients should be followed until puberty by periodic examination, until a situation of MDT is confirmed or definitively ruled out(10,12,15).

Fertility and cancer

The development and growth of the testicle at an abnormally high body temperature in the abdomen or inguinal region (37ºC) can cause early deleterious effects on the testicle, which justifies early treatment of these patients, during the first year of age. Possible alterations occur on testicular germ cells and their transformation into stem cells for future spermatogenesis, as well as on Leydig cells, which have been seen to decrease in histological studies of cryptorchid testicles(4,11). Thus, it has been shown that males with untreated cryptorchidism have impaired fertility, with a decrease in fertility rates, more likely if orchiopexy is performed after 18 months of age. In this regard, infertility rates of 10-30% have been described in patients with unilateral cryptorchidism, associated with azoospermia in 13% of cases, which increases to 90% in patients with untreated bilateral cryptorchidism(4). Likewise, alterations have been published in relation to testicular hypofunction, decreased testicular volume, sperm alterations and functional decrease of Leydig cells, in patients with a history of cryptorchidism(16).

In relation to testicular cancer, an increased risk of malignant degeneration in adulthood has been demonstrated in patients with a history of MDT, especially in those who were not treated before puberty and, more frequently, in testicles located intra-abdominally. Several studies and meta-analyses in fact report a significant reduction in the risk of testicular malignancy with prepubertal orchidopexy(4,17).

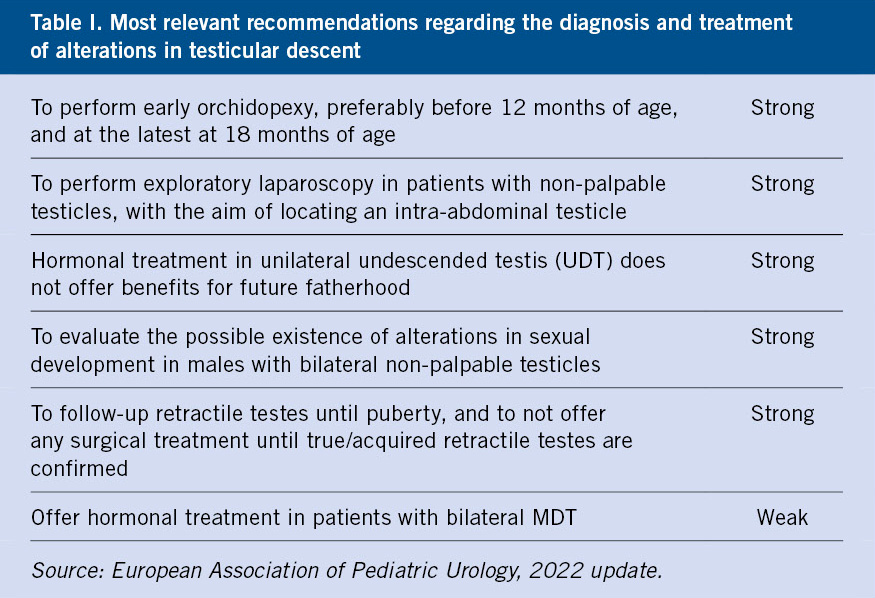

Table I summarizes the main recommendations related to the diagnosis and treatment of testicular descent disorders, according to the latest 2022 update of the European Association of Pediatric Urology.

Acute scrotum

Torsion of the testicular appendages, epididymitis and testicular torsion account for more than 80% of the causes of acute scrotum. Acute scrotum always requires urgent assessment to rule out testicular torsion, or urgent surgical examination if this is suspected.

It is defined by the clinical picture of testicular pain that has developed for a few hours, usually associated with local inflammatory signs such as swelling, erythema and/or increased scrotal temperature. Torsion of the testicular appendage, epididymitis or orchitis, or testicular torsion are the most frequent causes (80%), in that order.

Less frequent causes include: idiopathic scrotal edema (which may be painless), incarcerated hernia, testicular trauma, or other clinical conditions such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura or viral orchitis(18).

It always requires an urgent assessment to confirm or rule out the existence of testicular torsion, since without early treatment, it will lead to necrosis and atrophy of the testicle.

In the evaluation, it is very important to perform a correct physical examination and pay attention to certain signs or symptoms characteristic of each of these entities, which will guide us, together with the ultrasound data, to the diagnosis in each case. In this way, the evolution and location of the pain, more acute, severe and generalized in the testicle and scrotum in patients with testicular torsion, or located in the upper testicular pole in cases of torsion of the testicular appendages or in epididymitis, will guide us to the diagnosis in each case. On the other hand, cases of advanced neonatal testicular torsion may occur without associated pain.

Fever and detection of urinary tract infection should indicate an episode of orchitis or epididymo-orchitis, which occurs in approximately 20% of patients.

Testicular torsion

Testicular torsion is the third cause of acute scrotum. It is more frequent after puberty, caused by poor fixation and position of the testicle in the scrotum. Another peak of incidence occurs in the perinatal period, which may have occurred in utero or after birth.

Testicular torsion (TT) is caused by the rotation of the testicular cord on its longitudinal axis, causing a decrease or absence of vascularization of the testicle and, in advanced stages, testicular necrosis and atrophy. The time of evolution and the degree of torsion of the spermatic cord are the two main risk factors for testicular damage, having been shown that the risk of testicular necrosis occurs after 8-10 hours of evolution(4,19).

With an approximate incidence of 1/4,000 males (<25 years), it is the third most frequent cause of acute scrotum in the pediatric population (15-20%)(4,18,20), and must be differentiated in the diagnosis from testicular appendage torsion (leading cause of acute scrotum), since they may present with very similar initial symptoms, but with a very different progress, treatment and prognosis.

Testicular congestion and swelling in the early stages, caused by compression of the twisted venous vessels, evolves into ischemia and necrosis of the testicular parenchyma due to arterial obstruction as it progresses. This explains why, in the early stages, ultrasound can show a “false hypervascularization” due to congestion of the testicular coverings, with arterial flow still visible, although diminished, if the torsion is not complete. This fact must always be taken into account in cases of suspected testicular torsion, to avoid errors or delays in its diagnosis.

TT presents two incidence peaks: one less prevalent in the neonatal period (15%), and another more frequent from puberty between 12 and 18 years of age(4).

Depending on their origin and the position of the testicle and spermatic cord in relation to the vaginal tunic, the different types and clinical entities are classified(4,18,21):

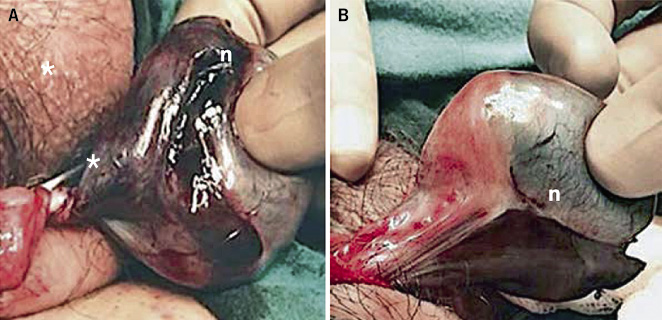

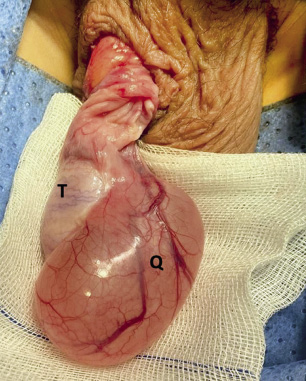

• Intravaginal torsion (Fig. 4): the most frequent and most common appearance around puberty (65%), although it can appear at any age. It is caused by poor, polar and narrow fixation of the testicle to the vaginal tunic, which predisposes to greater mobility of the testicle and its torsion on the axis of the spermatic cord inside the vaginal tunic in the scrotum. A typical deformity is the so-called “bell clapper testicle”, in which the testicle is arranged horizontally, suspended by the testicular cord inside the vaginal tunic, very mobile; and, therefore, with a greater predisposition to torsion. Its prevalence is estimated at 12% of males, being bilateral in 40% of cases.

Figure 4. Intravaginal testicular torsion. A 17-year-old adolescent with complete 360º torsion of the spermatic cord (asterisk), 12 hours after the procedure. A. Surgical exploration via the scrotum: necrosis (n) of the testicular parenchyma is observed. B. Scrotal detorsion with no signs of testicular viability, for which orchiectomy was indicated. Source: property of the author.

• Extravaginal torsion: it is caused by a rotation of the testicle and the vaginal tunic together on the axis of the spermatic cord in the inguinal region. It occurs in the prepubertal stage.

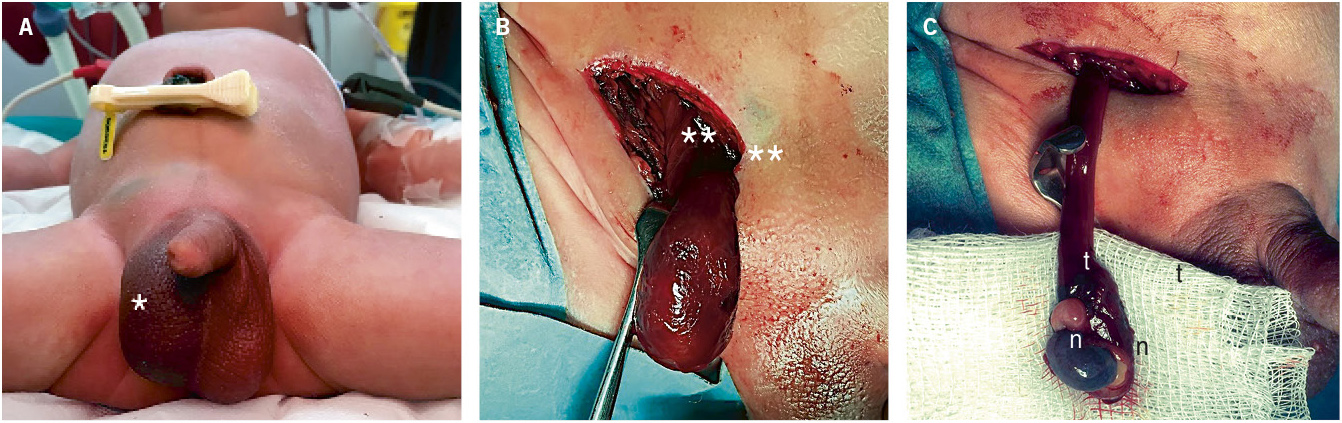

When diagnosed in the neonatal period, TT has occurred during gestation or at some point after birth, during the first month of life. It manifests as testicular torsion in up to 20% of cases, and accounts for 15-20% of TT cases. It should be noted that this may be underestimated, due to the fact that many cases are later diagnosed as cryptorchidism or testicular atrophy(21).

Depending on the moment of production of neonatal testicular torsion, two distinct entities are distinguished:

1. In utero Prenatal torsion, with a prolonged course and developed at the time of diagnosis (80%). It is not, therefore, considered an urgent clinical picture. It can be detected at the time of delivery or during the first examinations of the newborn. It usually presents as a hard inguinal or scrotal tumor, more or less painful and with inflammatory signs or not, depending on the evolution time. In cases with a longer evolution time, in which the torsion has occurred during the months of gestation remote from delivery, it is frequently diagnosed as cryptorchidism, as the already atrophic testicle cannot be palpated.

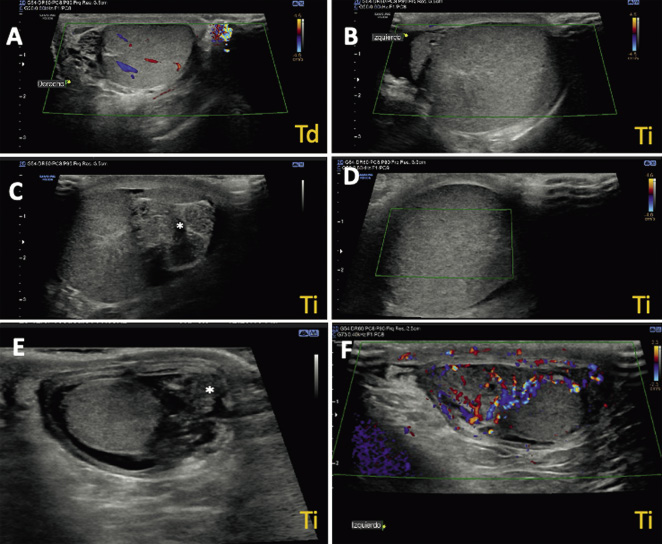

2. Postnatal torsion (Fig. 5): it occurs after birth and manifests as a picture of irritability, pain and acute scrotal syndrome, with erythema and scrotal swelling, in a newborn in whom previous examinations revealed a normal testicle. Treatment is urgent.

Figure 5. Neonatal testicular torsion. A. A 10-day-old patient was assessed for irritability, tenderness, swelling and scrotal induration (*). B. Extravaginal torsion of the testicle and tunica vaginalis over the spermatic cord, confirmed by inguinal examination (**). C. Testicular necrosis (n) and vascular thrombosis (t) of the spermatic cord after detorsion, requiring orchiectomy. Source: property of the author.

Epididymitis, orchitis and epididymo-orchitis

It is the inflammation of the epididymis, testicle or both, respectively. Orchitis usually appears associated with epididymitis due to the evolution of the latter. When it occurs in isolation, it occurs as a consequence of the hematogenous dissemination of a bacterial infection or secondary to a viral infection, such as mumps (orchitis urlianis), infections by adenovirus, enterovirus, influenza or parainfluenza(4). With an approximate annual incidence of 1.2/1,000 males, epididymitis/ epididymo-orchitis is the 2nd cause of acute scrotum in childhood (20-30%). In many patients, especially in prepubertal children, the origin is unknown, but in those cases in which repetitive episodes occur, the existence of malformations or urological functional disorders should be investigated. Vesicoureteral reflux, ectopic ureters or neurogenic bladder, as well as diagnostic tests that involve manipulation of the urinary tract (catheterization, cystography or cystoscopy) are risk factors to be taken into account in these cases. The germs most frequently isolated at this age are: E. coli, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, enterococci, enteroviruses or adenoviruses. In sexually active adolescents, epididymitis secondary to sexually transmitted infections (STDs) is the most frequent cause, with Chlamydia trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, E. coli and viruses being the most common causative microorganisms(22,23).

Torsion of the testicular and epididymal appendages

Torsion of the testicular appendage (Morgagni hydatid) is the most common cause of acute scrotum. Its treatment is medical, with surgical resection only being necessary in recurrent cases or those refractory to medical treatment.

It is the leading cause of acute scrotum (45%), and most commonly occurs in children between 7 and 12 years of age.

It is caused by torsion and secondary inflammation of the testicular or epididymal appendages (remnants of the Müllerian and Wolffian ducts), located in the upper pole of the testicle (Morgagni hydatid) or in the epididymis.

Other causes of acute scrotum

They account for 10-15% of cases of acute scrotum.

• Testicular trauma: high-impact testicular trauma can cause complications that affect testicular viability, so urgent assessment with testicular ultrasound is necessary. In addition to the production of testicular torsion secondary to trauma, the visualization of hematocele (hematoma in the tunica vaginalis), intratesticular hematoma or disruption of the tunica albuginea with rupture of the testicle, require surgical exploration to decompress the testicular parenchyma and prevent testicular necrosis.

• Incarcerated hernia: it may manifest as acute scrotal pain, as a result of pain radiating from the inguinal region. Occasionally, the intestinal contents of the hernia may be palpated in the scrotum.

• Henoch-Schönlein purpura: systemic vasculitis that may be associated with joint pain, abdominal pain, renal involvement, gastrointestinal bleeding and, occasionally, scrotal pain, both acute and insidious.

• Testicular tumor: although the most common mode of presentation of testicular cancer is the appearance of a painless testicular mass, intratumoral hemorrhage can cause acute testicular and/or scrotal pain, associated with inflammatory changes.

• Idiopathic scrotal edema: scrotal swelling, of short duration, with soft tissue swelling and local erythema. Typically, the patient is in good general condition and, if pain is reported, it is of low intensity. It is bilateral in >50% of cases, and recurrent in 10% of patients. The edema may extend to the perineum, inguinal region or penis. Ultrasound findings typically show hypervascularization and hypoechoic thickening of the scrotal sac, without alterations at the level of the testicle.

Diagnosis of clinical pictures of acute scrotum(4,19,22)

The diagnosis of acute scrotum should be based on the history and physical examination. In cases of suspected testicular torsion, the recommended approach is surgical examination, without carrying out additional tests that delay early treatment.

History and physical examination

They are considered essential in the diagnosis of acute scrotum, since there are characteristic clinical signs and data for each of the clinical entities, which will guide to the diagnosis. The physical examination is based on inspection and palpation of the testicle and scrotum, bilaterally. Attention should be paid to the position of the testicle, the intensity and location of the pain, the presence of inflammatory signs, and the assessment of the cremasteric reflex. Reactive hydrocele is frequently observed, which is more characteristic of testicular torsion, advanced epididymitis or testicular trauma.

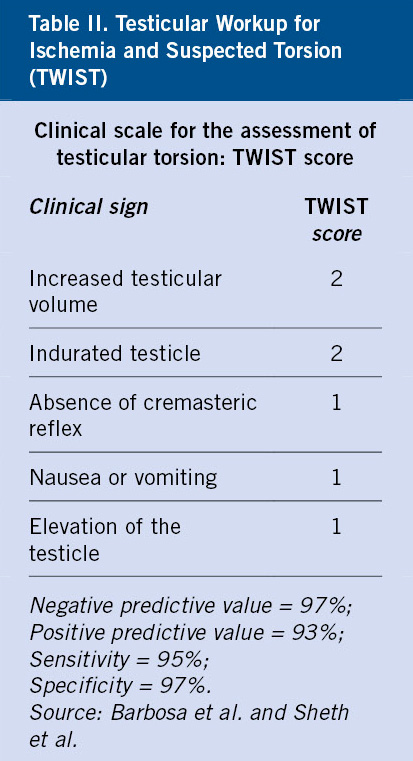

In the clinical evaluation of the acute scrotum, the TWIST (Testicular Workup for Ischemia and Suspected Torsion) score has been developed to identify patients at risk of developing testicular torsion. This scale assesses: testicular swelling and consistency, cremasteric reflex, testicular position and the presence or absence of nausea or vomiting (Table II). With values ranging from 0 to 7 (maximum probability of TT), it has been validated as a reliable and useful scale in the diagnosis of testicular torsion, given its sensitivity and specificity(19).

In addition, it is important to investigate certain aspects in the history that may predispose to episodes of acute scrotum, including:

• Background of testicular maldescent; scrotal trauma/strenuous physical activity: testicular torsion.

• Sexual activity; malformations, urological functional anomalies; manipulation of the urinary tract; previous infectious episodes or systemic diseases (vasculitis): epididymitis/epididymo-orchitis.

Among the clinical data to be taken into account, the following are highlighted:

• Age: important factor in the differential diagnosis of acute scrotum, since the frequency of appearance is different according to the diverse pathologies. Thus, testicular torsion, with a bimodal distribution pattern, is more frequent in adolescence, a period in which episodes of epididymo-orchitis are also more prevalent. Testicular hydatid torsion occurs more frequently in the prepubertal stage.

• Pain: intensity, duration and association with other symptoms. Testicular torsion typically manifests itself with intense pain, sudden onset, lasting a few hours. In addition, the patient is in poor general condition and may have other symptoms such as nausea or vomiting.

In the case of torsion of the testicular hydatids or epididymitis, the pain, located in the upper pole of the testicle, follows a more gradual course, is not as intense and, typically, the patient remains in good general condition. In the case of torsion of the testicular appendix, the pain is very limited to one point in the upper pole of the testicle.

In addition, in both testicular torsion and epididymitis, there may be pain radiating to the inguinal region.

It should not be forgotten that evolved neonatal torsions may occur without associated pain(21).

• Fever: it is not a frequent symptom in the acute scrotum. It appears in <20% of cases of epididymo-orchitis. An exception is the case of orchitis of viral origin, in which a history of febrile syndrome is frequent, a few days prior to the episode of acute scrotum.

• Urinary symptoms: the presence of symptoms such as dysuria, pollakiuria or bladder tenesmus should indicate the presence of epididymitis. If there are also clinical signs of urethritis, we should suspect epididymitis secondary to STDs in adolescents.

In relation to the physical examination, the following data are noteworthy in some entities:

• In testicular torsion: scrotal erythema and swelling are very evident, together with increased testicular consistency, which is very painful to palpation (Fig. 3). The testicle appears “fixed”, horizontalized and raised, with the epididymis in an anterior position: “Gouverneur sign”. In addition, the cremasteric reflex is usually abolished; although its presence does not rule out the existence of testicular torsion. It is also important to remember that the cremasteric reflex may be physiologically absent in patients under 6 months of age.

In patients with torsion of an undescended testicle, the painful testicle is palpated in the inguinal region with local inflammatory signs and an ipsilateral empty scrotum.

• In epididymitis, the pain is maximum on palpation in the area corresponding to the epididymis, which appears thickened. It can extend to the rest of the testicle in epididymo-orchitis. The testicle is mobile within the scrotal sac, is normally positioned and maintains the cremasteric reflex, although the latter may be difficult to assess in cases with severe inflammation. Prehn’s sign: the pain is relieved by raising the testicle (contrary to what occurs in testicular torsion: the pain does not decrease or even increases with testicular elevation).

• In testicular hydatid torsion, the pain is located in the upper pole of the testicle. Erythema and heat of the scrotal skin may or may not be associated to varying degrees. The characteristic sign of the “blue dot” is observed in the upper pole of the testicle when performing scrotal transillumination and corresponds to necrosis or congestion of the twisted appendix. The presence of the blue dot (10-23% of cases) is a characteristic sign of hydatid torsion, but its absence (when there is inflammation of the hydatid, but necrosis has not occurred) does not rule it out.

Table III summarizes the most characteristic clinical data of testicular torsion, hydatid torsion and epididymitis in the differential diagnosis of acute scrotal conditions.

Complementary tests

The first objective in the diagnosis of acute scrotum is to confirm or rule out whether we are dealing with a case of testicular torsion and, in this situation, the patient should be evaluated by a specialist in Pediatric Surgery.

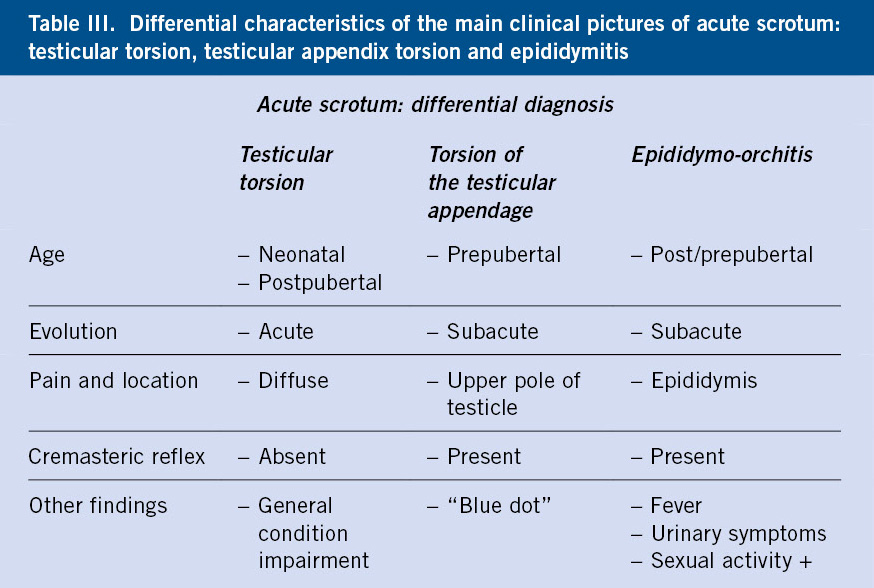

Ultrasound associated with testicular Doppler is the imaging test of choice in the diagnosis of acute scrotum (Fig. 6), but it must be taken into account that, given the high diagnostic suspicion of testicular torsion, the approach to follow is urgent surgical exploration, the only diagnostic measure of certainty, which will also be therapeutic in the event that testicular torsion is confirmed. It is important to insist that, although ultrasound is the gold standard technique in the diagnosis of testicular pathology, surgical treatment should never be delayed in cases that suggest TT, pending its performance. In addition, although arterial flow is decreased or absent in the torsioned testicle, in the initial phases it may be preserved, and hypervascularization of the testicular coverings may also be associated due to venous congestion and the inflammatory process itself, which may lead to errors (false negatives) in the diagnosis of TT. This is also why ultrasound findings should never change the indication for urgent surgical exploration when testicular torsion is suspected, even if the Doppler study reports the presence of testicular discharge.

Figure 6. Bilateral testicular Doppler ultrasound in left testicular torsion (A, B, C and D) and epididymitis (E and F). A. Right testicle (Td) with normal ultrasound appearance, with preserved arterial flow. B, D. Left testicle (Ti) with signs of testicular torsion: enlarged size and absence of flow on Doppler study. C. Left testicle (Ti) in which the turn of the spermatic cord can be seen (asterisk). E. Left testicle with epididymitis. The thickening of the epididymis is marked with an asterisk. F. Hypervascularization of the coverings of the left testicle with epididymitis. Source: property of the author.

Bilateral testicular ultrasound also allows for the assessment of symmetry in relation to the size, location and appearance of the testicular parenchyma, thickening and position of the spermatic cord, thickening of the testicular coverings and the scrotal sac, or size and inflammatory signs of the testicular appendages or the epididymis.

It should also not be forgotten that Doppler ultrasound can provide false positive diagnoses of testicular torsion in situations such as large tension hydroceles, inguinoscrotal hernias or large testicular hematomas, which hinder testicular vascularization.

Urinalysis should be performed in cases of epididymitis and epididymo-orchitis. If leukocyturia or positive nitrites are observed, or the patient presents clear urinary symptoms, a culture with antibiogram will be performed to validate the empirical antibiotic treatment initially prescribed. It is important to note that a positive urine analysis and culture is obtained in a low percentage of patients with epididymitis and, on the contrary, the normality of the results of these tests does not exclude the diagnosis of epididymitis. Likewise, a pathological urine test does not exclude testicular torsion. Additionally, the collection of urethral exudate for microbiological study is indicated in adolescents with sexual activity, and suspected epididymitis as a sexually transmitted disease (STD).

Treatment of acute scrotum

Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency that requires early surgical treatment to ensure testicular viability. The degree of torsion and the time of evolution are the two main factors in predicting testicular damage. In contrast, in Morgagni hydatid torsion, the indicated treatment is medical, with rest and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency that requires early treatment to preserve testicular viability. The two determining factors of testicular damage are the degree of torsion and the time of evolution, with recovery of the testicular parenchyma being more likely when detorsion is performed in the first 4-8 hours of evolution. In cases of complete torsion, the risk of testicular necrosis is very high with a short evolution time (4 h), and when the torsion is incomplete, there is a possibility that the testicle remains viable, with evolutionary courses of up to 12 hours(4,18,19).

The surgical intervention consists of manual detorsion of the testicle and fixation of the same in the scrotum: orchidopexy, if its viability is confirmed during the surgical exploration. Currently, contralateral orchidopexy is recommended in the same procedure, given the risk of future torsion on that side(4).

If the testicle is necrotic, removal of the testicle is indicated: orchiectomy, and fixation of the contralateral testicle in the scrotum. For the treatment of intravaginal torsion, the approach is performed through a scrotal incision, while in the case of extravaginal torsion, this is done via the inguinal route.

Manual detorsion can be attempted before surgery, by external rotation of the testicle (a maneuver similar to opening a book) if there is no resistance or increased pain. In cases where the maneuver succeeds in detorting the testicle, the pain disappears. In this situation, urgent surgical exploration should also be indicated in case partial torsion remains.

Patients with intermittent torsion suffer episodes of testicular torsion that resolve spontaneously within seconds or minutes of the onset of the condition. Testicular examination and ultrasound may be normal at the time of clinical assessment, if the condition has resolved. Follow-up and surgical treatment by orchidopexy are indicated to prevent future episodes.

In cases of neonatal torsion, bilateral surgical exploration and orchidopexy are indicated due to the possibility of bilateral torsion in up to 20% of cases.

In the case of prenatal torsion, there is no consensus regarding the time of surgical intervention and surgical exploration of the contralateral side. Although the affected testicle is necrotic in almost all cases and, therefore, does not represent a surgical emergency, the objective of treatment is scrotal fixation of the contralateral testicle to prevent future torsion. Taking into account also the possibility of undiagnosed cases of synchronous bilateral torsion, surgical treatment is generally recommended as a priority when the patient is stable and there are no clinical or anesthetic contraindications to performing it(21).

Monitoring and evolution of testicular torsion

In general, the risk of testicular torsion recurrence is <5%, and it may occur years after the first episode. Furthermore, despite adequate detorsion and the appearance of testicular viability during the surgical procedure of the acute episode, some patients develop testicular atrophy over time, which may affect their future fertility. This situation may be due to both direct damage to the testicular parenchyma by ischemia during torsion, and rapid reabsorption of free radicals in the testicle during the post-ischemia reperfusion phase. These changes could lead to implications for future fertility, which are more frequent in cases of severe and advanced testicular torsion(4,19).

In epididymitis/epididymo-orchitis, the treatment of choice is medical with rest and anti-inflammatory drugs, and antibiotic therapy is not generally indicated, unless there is suspicion of urinary tract infection following the results of the urine test and culture(4). In these cases, we propose starting empirical antibiotic treatment according to the current recommendations published by the Spanish Association of Primary Care Pediatrics(23) (ABE Guide: https://www.guia-abe.es/).

Initial treatment with coverage for Gram + and Gram – is therefore established with 2nd/3rd generation cephalosporins (cefuroxime: 20-30 mg/kg/day; cefixime: 8 mg/kg/day), amoxicillin-clavulanate (50 mg/kg/day) or quinolones in older children (ciprofloxacin: 20-40 mg/kg/day; levofloxacin: 500 mg/day), for 7-10 days. These treatments will be re-evaluated based on the results of the culture and antibiogram.

In testicular hydatid torsion, medical treatment with rest and anti-inflammatory drugs is also established as the first option. Improvement is usually progressive until the clinical picture is resolved in 7-10 days. Surgical treatment is only indicated for the removal of the testicular/epididymal appendix in cases of pain refractory to medical treatment or in those patients with recurrent episodes. Surgical exploration of the contralateral testicle is not indicated(22).

In patients with testicular trauma, rest and analgesic and anti-inflammatory treatment are indicated. In cases of rupture, compressive hematoma or suspected testicular torsion, surgical exploration is indicated.

Idiopathic scrotal edema does not usually require treatment, except in patients who present with local painful discomfort, who will be treated with anti-inflammatory treatment(24).

Acute scrotal assessment by the pediatrician: important aspects to consider

• The main goal of the pediatrician in the evaluation of the patient with acute testicular pain should be to identify symptoms and signs that may suggest the existence of testicular torsion. At the slightest suspicion, urgent evaluation by Pediatric Surgery should be indicated.

• The diagnosis of acute scrotum is clinical and additional tests that may delay early surgical treatment of a possible case of testicular torsion are not indicated.

• Scrotal and testicular ultrasound with Doppler study is the imaging test of choice in the assessment of scrotal and testicular pathology. In cases of acute scrotum, it helps to assess the flow and testicular parenchyma, the degree of inflammation in cases of severe epididymitis or the detection of an inflamed appendix in the torsion of testicular/epididymal appendages.

• In cases of epididymitis in prepubertal children, systematic antibiotic treatment is not justified, except in the case of urinary symptoms, pathological urine examination or a history that suggests the presence of a urinary tract infection. In most cases, where these circumstances do not occur, symptomatic treatment with rest, anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics is indicated.

Epididymitis in adolescents with an active sexual life should be treated empirically with antibiotic therapy that cover N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, to cover sexually transmitted infections.

In cases of orchitis/epididymitis with a strong inflammatory component, torpid evolution despite medical treatment, or the appearance of general symptoms, evaluation by the Surgery team is indicated, who will assess the indication of intravenous antibiotic treatment and the performance of a testicular ultrasound to study the involvement of the testicular parenchyma.

• In patients with clear symptoms of testicular hydatid torsion, rest and symptomatic treatment with oral anti-inflammatory drugs will be indicated. Surgical treatment is indicated in cases of persistent pain that is refractory to medical treatment or in cases of recurrent pain.

• Moderate-severe testicular trauma should be assessed by performing testicular ultrasound and urgent care by the Surgery team, to assess parenchymal involvement and/or possible complications requiring surgical treatment, such as rupture, tension hematoma or testicular torsion. The same approach should be followed in cases of testicular tumor, in order to rule out the existence of a possible testicular tumor.

Other causes of scrotal pathology

Hydrocele(4)

It is defined as the accumulation of liquid content between the visceral and parietal layers of the testicular vaginal tunic. On physical examination it is identified as an increase in scrotal volume, with positive and painless transillumination (when not associated with testicular inflammatory processes). It may be primary, malformative or due to hypersecretion, or secondary to other inflammatory processes of the testicle, such as testicular torsion, epididymo-orchitis or testicular trauma. It may also occur after varicocele operations due to ligation of lymphatic vessels during the intervention.

In this section we will refer to primary hydrocele, which is classified as:

1. Congenital hydrocele: it appears in childhood, and is caused by the persistence of the vaginal process (pvp).

2. Hydrocele of the adult: generated by the accumulation of fluid due to hypersecretion of the vaginal mucosa and the imbalance between this production and its reabsorption. It should be suspected when it occurs around adolescence, in patients with no history of hydrocele or inguinal hernia during childhood.

In the case of congenital hydrocele, this may appear as a communicating hydrocele: in which the vaginal process remains open throughout its length and is therefore oscillating, being more evident at the end of the day. In other cases, the pvp is obliterated at some point, giving rise to a fixed, non-reducible tumor, visible in the inguinal region (spermatic cord cyst), or in the scrotum, depending on the location of the closure of the vaginal process.

The diagnosis of hydrocele is clinical and no additional complementary tests are necessary, except in cases where an association with other pathologies is suspected, such as a testicular mass or any testicular inflammatory condition.

In patients with congenital hydrocele, spontaneous obliteration must be awaited during the first year or two of life. From this point on, treatment is surgical and consists of ligation and section of the vaginal process through an inguinal approach, a procedure called herniorrhaphy, since it is the same procedure performed in the treatment of inguinal hernia. As an alternative approach, laparoscopic herniorrhaphy may be indicated, depending on the experience and preferences of the surgeon.

It is important to remember that hydrocele does not cause testicular damage, so surgery is scheduled from one year of age, without being urgent.

As an exception, in cases where concomitant inguinal hernia is suspected, surgical treatment is indicated at the time of diagnosis.

In the case of non-communicating scrotal hydrocele of the adult, the surgical treatment is hydrocelectomy via the scrotum: drainage of the hydrocele by opening and sectioning the tunica vaginalis.

Varicocele

Varicocele in adolescents is usually asymptomatic. Treatment criteria include the appearance of symptoms (pain) or decreased testicular growth.

This is the dilation of the testicular veins in the pampiniform plexus caused by venous reflux. It most commonly appears after puberty (15-20% in adolescents), but is rare in children under 10 years of age. In 90% of cases, it appears on the left side, and may be bilateral in some patients(25). The anatomical arrangement of the left spermatic vein at its junction with the left renal vein at a 90º angle has been described as one of the causes.

Depending on their severity, 3 degrees are differentiated according to the Dubin-Amelar Classification:

• Grade I: palpable varicocele with Valsalva maneuver.

• Grade II: palpable varicocele (without Valsalva maneuver).

• Grade III: visible varicocele.

Subclinical varicocele is one that is detected only on ultrasound, incidentally, with no findings during physical examination.

In adolescents, varicocele is usually asymptomatic and develops little, but close clinical and ultrasound monitoring is essential for early diagnosis of symptoms such as testicular pain or decreased testicular volume, which are indications for treatment. As a long-term complication, it has been reported that 20% of adolescents with varicocele may develop fertility problems in the future, secondary to hypogonadism and decreased testosterone secretion, generated by parenchymal damage to the testicle exposed to an abnormally high temperature.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on:

• Physical examination: varicocele is detected by visualization and/or palpation of dilated and tortuous testicular veins in the standing position, which become more evident with Valsalva maneuver.

• The size of both testicles should always be assessed in the search for asymmetries due to decreased testicular volume on the side of the varicocele.

• Ultrasound-Testicular Doppler: it confirms the presence of varicocele and its severity. It measures venous reflux in the pampiniform plexus in the standing and supine positions; and testicular size, considering a sign of hypoplasia when testicular volume is <20% with respect to the contralateral volume.

Abdominal ultrasound should be performed in patients with a more “atypical” presentation of varicocele, in whom it is necessary to rule out the existence of a tumor mass as a cause of varicocele, due to compression of the renal vein or the inferior vena cava. In this sense, it should be indicated especially in prepubertal patients or in cases of isolated right varicocele.

Treatment

It has been shown that treatment of varicocele improves testicular volume, seminal parameters and the chances of future fertility. The success of treatment in terms of the disappearance of varicocele is 85-100% of patients depending on the different techniques and the experience of each center. Therefore, two main treatment criteria have been established for varicocele in childhood and adolescence, which are the following:

1. Varicocele associated with decreased testicular size (hypotrophy).

2. Symptomatic varicocele.

Furthermore, alterations in the study parameters of semen samples, or other situations, such as bilateral palpable varicocele or the association of other pathologies with risk of fertility, could also be assessed, as other indications for treatment in varicocele(4,26-29).

Treatment options include various surgical techniques of ligation and vascular section or endovascular embolization, as a non-surgical alternative. Due to the lack of studies in pediatrics, significant differences in the therapeutic results of the different techniques have not been confirmed, which depend largely on the experience of each center. Therefore, there is still controversy regarding the best method of treatment of varicocele in pediatric and adolescent patients.

Embolization is performed by means of a percutaneous endovascular procedure, consisting of the introduction of metal coils or sclerosing substances into the spermatic veins, through the catheterization of a main vein in the groin (femoral vein), the neck (internal jugular vein) or the arm (basilic vein). Due to the selective action on the venous vessels, it has the advantage of not subsequently developing hydrocele due to injury to the lymphatic vessels of the spermatic cord, the most frequent complication of surgical treatment. As it is a minimally invasive technique, in most patients it is also considered a short-stay intervention, which does not require admission in most patients. On the other hand, and despite being an effective treatment with success rates of around 80-90%(25,29), its main disadvantage is a higher recurrence rate (13-15%) compared to surgical treatment (5-7%), which makes it necessary in some patients to repeat the embolization.

Surgical treatment consists of ligation and section of the dilated spermatic veins, using an inguinal, retroperitoneal or laparoscopic approach. Ligation of the spermatic veins can be performed selectively, with preservation of the spermatic artery (Ivanissevich technique – inguinal approach), or together with the spermatic artery (Paloma technique – retroperitoneal approach). In the case of the laparoscopic approach, either of the two options can be used. In the latter case, the technique can be optimized by intra-testicular injection of coloring substances (e.g., indocyanine green), which stains the lymphatic vessels of the spermatic cord, allowing their preservation and preventing the appearance of postoperative hydrocele.

Complications of varicocele treatment are rare. As mentioned above, post-surgical hydrocele is the most frequent, with rates of 5-10%, which decrease significantly with preservation of the lymphatic vessels. Other rarer complications described are: testicular atrophy after ligation of the spermatic artery or migration of the embolization material to the renal vein with thrombosis of the same.

Epididymal cysts and spermatocele (Fig. 7)

Figure 7. Epididymal cyst in a 15-year-old patient. Surgical resection was indicated due to its large size, the impossibility of differentiating the testicle from the cyst during physical examination (which made a correct testicular examination difficult in the presence of other scrotal pathologies), and the presence of painful discomfort with exercise. Source: property of the author.

Epididymal cysts are benign in origin, appear in any area of the epididymis and are filled with a clear fluid that does not contain sperm. They are more common in prepubertal males. They are often asymptomatic, small in size and are usually diagnosed incidentally during physical examination or testicular ultrasound performed for other reasons. Their etiology is unknown in most cases, although a history of testicular trauma or epididymitis has sometimes been described. They may disappear spontaneously.

They must be differentiated from spermatocele, which is indistinguishable on physical examination and also manifests as an epididymal cyst, which appears in post-pubertal stages and contains sperm inside. They appear in the head of the epididymis and, although they are usually asymptomatic, they can cause pain in a higher percentage than epididymal cysts in childhood. On ultrasound, they can be differentiated from these by having content with variable echoes and septa inside.

The differential diagnosis of epididymal cysts must be made with other testicular pathologies of a different nature such as: epididymitis, hydrocele, varicocele or testicular tumors.

Observation is the measure indicated as a first option, both in epididymal cysts and in spermatocele that appears in asymptomatic patients, without diagnostic doubts or with small cysts (<10 mm). On the contrary, epididymal cysts or spermatoceles, of large size, or of progressive growth, with diagnostic doubts or associated pain, are treated surgically by complete removal of the cyst, via the scrotum(30).

Role of the Primary Care pediatrician

The primary goal of the primary care pediatrician in the assessment of testicular descent problems should be their early identification in order to indicate their follow-up by the pediatric surgeon in case of suspicion, doubt or confirmation. This will allow treatment around one year of age, thus avoiding possible consequences that may occur on fertility in the future. In cases where they are identified late, they should also be referred for treatment before puberty, thus minimizing the potential risks of testicular malignancy.

To this end, the primary function is to carry out an adequate examination of the inguinoscrotal region, both during the programmed well-baby check-ups and in other cases that occur due to any other symptom or sign related to the testicle, scrotum, inguinal or abdominal region. In addition, it is very important for the pediatrician to be familiar with the surgical calendar, in relation to the recommendations on the time to establish the diagnosis of cryptorchidism according to gestational age or with the differentiation between true cases of MDT from those of retractile testicles, which do not require any type of treatment.

In the case of acute scrotal symptoms, and at the slightest suspicion of testicular torsion, the immediate request for urgent assessment by Pediatric Surgery from the Primary Care consultation is vital in order to be able to carry out an urgent surgical examination and the recovery of the testicle, in the event that this is confirmed. In this case, prior complementary tests should not be requested, as they would delay the diagnosis.

Regarding varicocele, the primary care pediatrician should consider it an alarm sign when it appears on the right side, and request a preferential abdominal ultrasound to rule out the existence of an abdominal mass.

In cases of recurrent epididymo-orchitis in prepubertal patients, the existence of malformative or functional disorders of the urinary system should be investigated, which should be initiated by performing an ultrasound at that level.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest in the preparation of the manuscript.

Bibliography

The asterisks indicate the interest of the article in the author’s opinion.

1. Barthold JS, González R. The epidemiology of congenital cryptorchidism, testicular ascent and orchiopexy. The Journal of Urology. 2003; 170: 2396-401.

2. Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Villanueva CA. Cryptorchidism. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available in: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470270/.

3.*** Shin J, Jeon GW. Comparison of diagnosis and treatment guidelines for undescended testis. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020; 63: 415-21.

4.*** Radmayr C, Bogaert G, Burgu B, Dogan HS, Nijman JM, Quaedackers J, et al. EAU Guidelines on Pediatric Urology. European Association of Urology. 2022. Available in: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/paediatric-urology.

5.** Chedrawe ER, Keefe DT, Romao RLP. Diagnosis, Classification, and Contemporary Management of Undescended Testicles. Urol Clin North Am. 2023; 50: 477-90.

6. Muíños CC. Cryptorchidism and testicular-scrotal pathology in pediatric age. Criptorquidia y patología testículo-escrotal en la edad pediátrica. Pediatr Integral. 2019; XXIII: 271-82. Available in: https://www.pediatriaintegral.es/publicacion-2019-09/criptorquidia-y-patologia-testiculo-escrotal-en-la-edad-pediatrica/.

7.** Echeverría Sepúlveda MP, Yankovic Barceló F, López Egaña PJ. The undescended testis in children and adolescents part 2: evaluation and therapeutic approach. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022; 38: 789-99.

8. Hutson JM. Cryptorchidism and Hypospadias. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, et al., eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2022. Available in: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279106/.

9.*** Hutson JM, Vikraman J, Li R, Thorup J. Undescended testis: What paediatricians need to know. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017; 53: 1101-4.

10. Boehme P, Degener S, Wirth S, Geis B, Aydin M, Lawrenz K, et al. Multicenter Analysis of Acquired Undescended Testis and its Impact on the Timing of Orchidopexy. J Pediatr. 2020; 223: 170-177.e3.

11. Park KH, Lee JH, Han JJ, Lee SD, Song SY. Histological evidences suggest recommending orchiopexy within the first year of life for children with unilateral inguinal cryptorchid testis. Int J Urol. 2007; 14: 616-21.