|

| Topics on Continuous Training |

T. Pozo Román*, B. Mínguez Rodríguez**

*Lead of the Dermatology Unit at Río Hortega University Hospital. Valladolid. **Consultant in Pediatrics at San Joan de Deu Hospital. Barcelona

| Abstract

Atopic dermatitis is a common and frequently familial inflammatory dermatosis, which usually appears during infancy or early childhood and is often associated with other atopic diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, food allergies or eosinophilic esophagitis. It is a complex genetic disease with environmental influences, characterized by intense pruritus and a chronic course in flares. |

Key words: Atopic dermatitis; Eczema; Atopy; Seborrheic dermatitis; Malassezia (Pityrosporum).

Palabras clave: Dermatitis atópica; Eczema; Atopia; Dermatitis seborreica; Malassezia (Pityrosporum).

Pediatr Integral 2021; XXV (3): 119 EN – 127 EN

Atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis

Introducción/definición

Atopic dermatitis is characterized by flares of inflammatory, itchy lesions, with a characteristic distribution and personal and / or family history of atopy (allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma, food allergies, etc.).

Atopic dermatitis (AD) and food allergy have a predilection for infants and young children; whereas, asthma prevails in older children and rhinoconjunctivitis predominates in adolescents. This characteristic age-dependent sequence is called “atopic march”, however, it does not always manifest, as these diseases may or may not appear, and do so simultaneously or at different ages.

It is more prevalent in children (10-20%) than in adults (1-3%) and, in 90% of cases, it appears in childhood (45% during the first 6 months of life and 60% before the first year of life). At least 50% of atopic children will continue to express certain manifestation of the disease during adolescence and 20% also in adult life(1,2).

Most of the cases can be considered mild, but 10% of the patients suffer a severe form which is more prevalent in the adult population. The prevalence of severe atopic dermatitis in adults in Spain is estimated to be 0.08%(3).

In the most severe forms, the sleep cycle is disturbed leading to irritability, which affects school and sport performance, self-esteem, social relationships, as well as routine and leisure activities.

On the other hand, AD, and especially severe AD, implies a significant economic expense, both direct (medical visits, pharmacological cost) and indirect costs (loss of school hours and productivity), and both at a personal level as well as for health systems. This emphasizes the need to evaluate its impact on the family environment and on the patients’ caregivers. Hence, it should be recognized as a “family” disease, rather than as an individual one and, as such, it must be evaluated(4).

Etiopathogenesis

A deficient skin barrier action, an abnormal immune response, alteration of the cutaneous microbiome and an important psychosomatic influence are the main etiopathogenic factors.

It is a complex genetic disease, with interactions between different genes and of these with the environment.

In patients with AD, the lesional skin and, to a lesser extent, the non-lesional skin, present a defective cutaneous barrier, with: increased transepidermal water loss, alteration of skin lipids, increased epidermal proliferation, reduction of Filaggrin expression, inflammation, and increased number of IgE receptors on Langerhans cells.

The uninjured skin also shows different immunological profiles to normal skin (17% more T cells than normal skin and increased expression of Th1, Th2 and Th22 lymphocytes). Antigens that cross the skin reach the ganglia (via dendritic cells) and stimulate Th2 response with the consequent increase in the production of IgE and several other mediators from various inflammatory and epidermal cells. Immunity mediated by the Th1 pathway (which is attenuated) and the innate immune system contribute to skin inflammation with the release of cytokines and a deficiency of antimicrobial peptides.

Patients with AD show important changes in skin microbiome, mainly involving a decrease in Staphylococcus Epidermidis and a dominant colonization of Staphylococcus Aureus (in up to 90% of the lesions), which correlates with the severity of the disease. Conversely, recovery of microbiome diversity precedes resolution of flare-ups.

All these abnormalities interact with each other; so that: barrier dysfunction alters the skin’s microbiome and immune response; the skin microbiome alters the immune response and the skin barrier; and, lastly, immune dysregulation also alters the cutaneous microbiome and the skin’s barrier function(5).

Manifestations and diagnosis

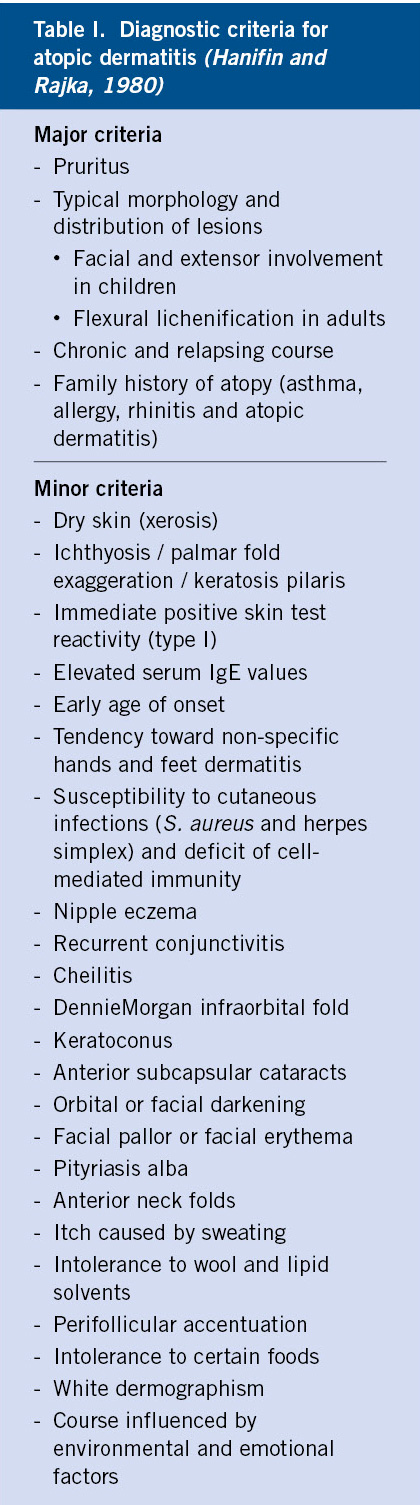

The diagnosis of AD is mainly clinical and remains based on the classical criteria described by Hanifin and Rajka(6): 3 or more major criteria, and 3 or more minor criteria (Table I).

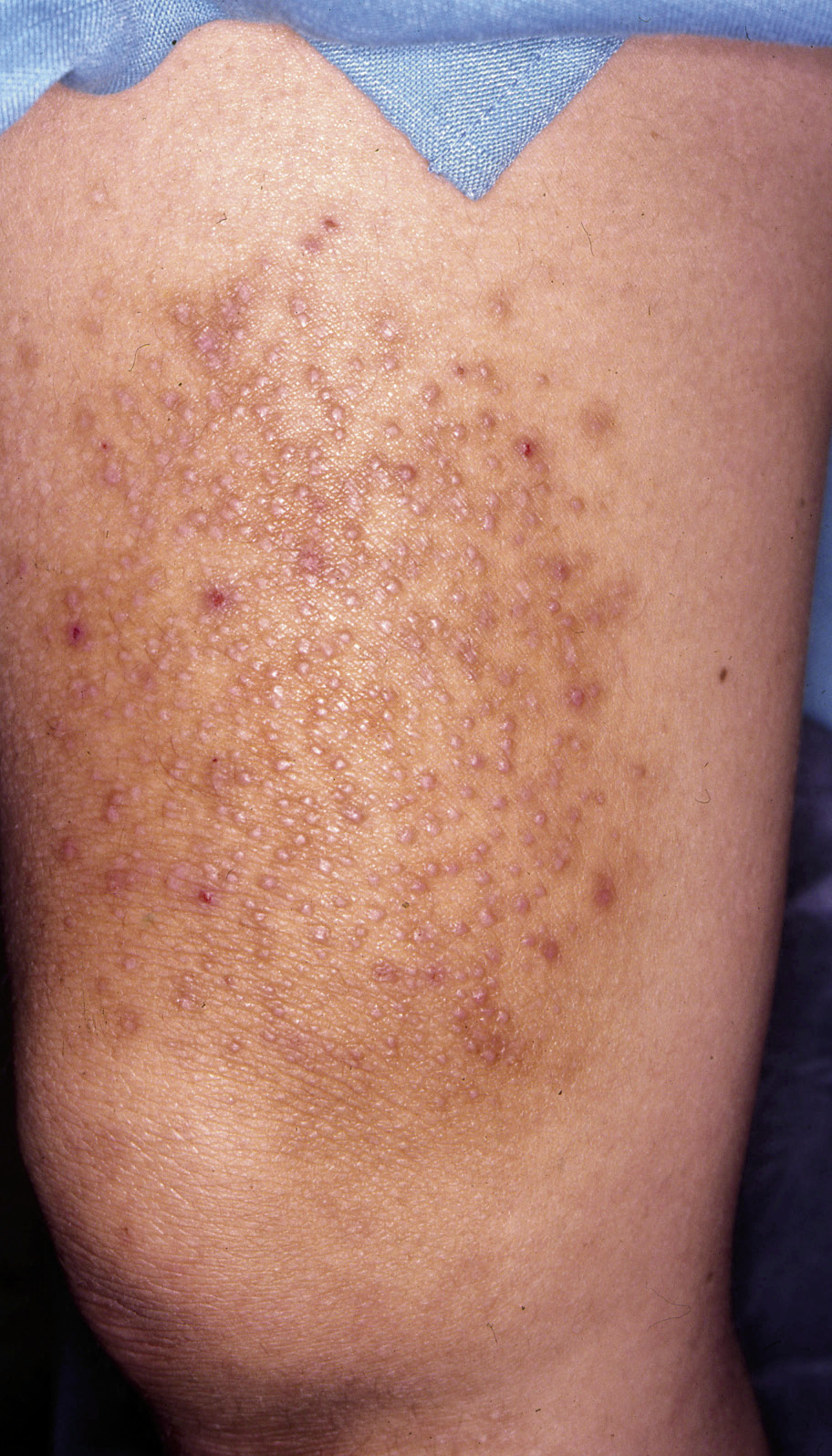

The diagnosis of AD is primarily clinical (Figs. 1-5).

Figura 1. Atopic dermatitis in the acute phase.

Figura 2. Impetiginized eczema.

Figura 3. Retroauricular eczema with fissuring.

Figura 4. Labial and perioral eczema.

Figura 5. Chronic eczema from scratching (neurodermatitis).

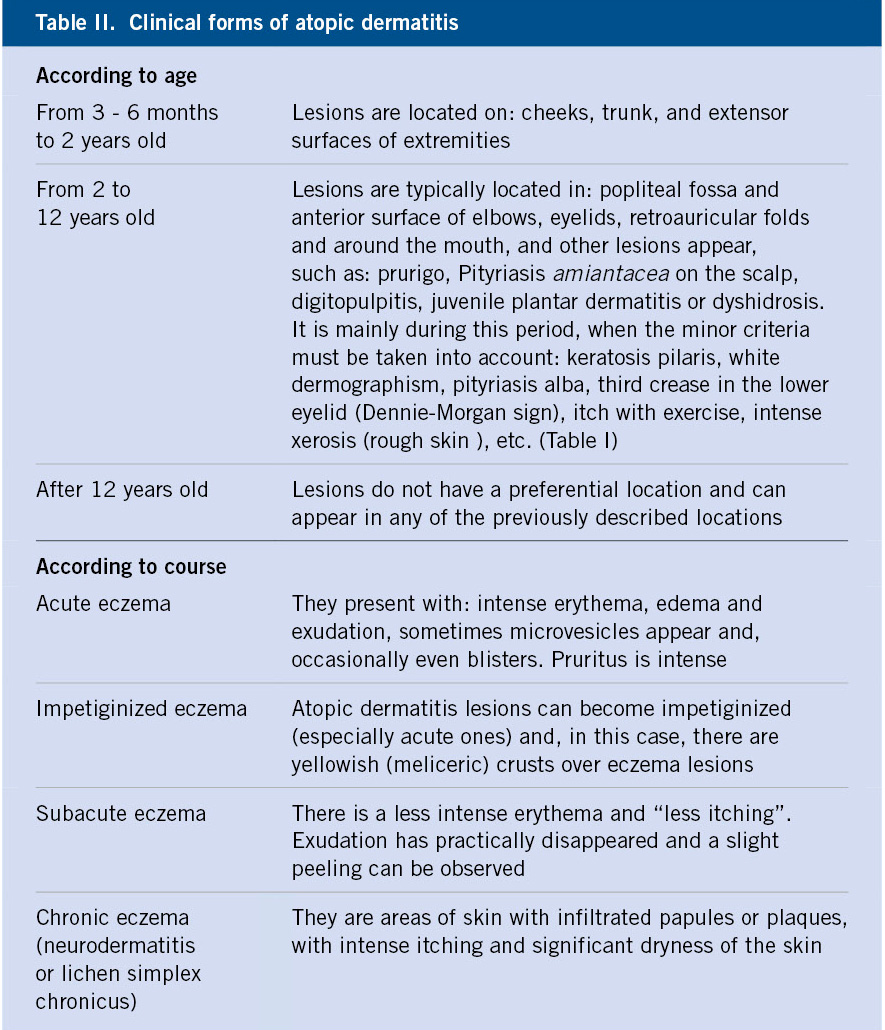

Characteristically, the typical lesions of atopic eczema are erythematous areas of skin, often poorly defined, with intense itching, although their distribution and characteristics vary with age. There are also some characteristic clinical manifestations that must be known (Table II).

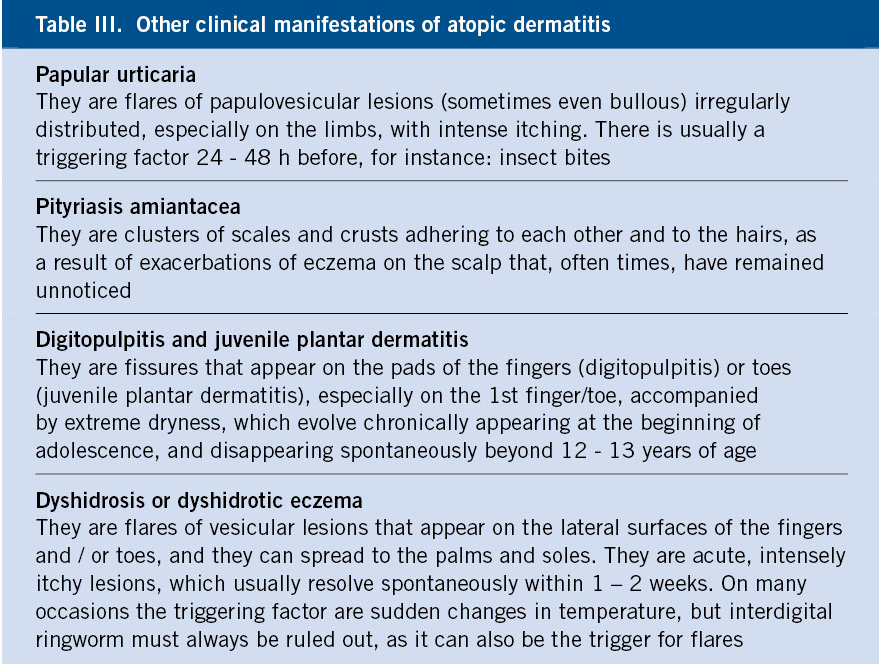

It is also important to distinguish between acute, subacute and chronic forms, as the topical treatment differs (Table II) and to identify other clinical manifestations of AD, which are very common (Table III).

Differential diagnosis

The symptoms of AD are highly characteristic, thus most of the possible differential diagnoses can be excluded by the medical history (scabies, seborrheic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis and ichthyosis).

In some cases, it may be necessary to perform biopsies (cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and psoriasis) or to perform contact tests (allergic contact or airborne dermatitis), or special studies (photosensitive diseases, diseases due to deficiencies of the immune system, erythroderma due to other causes, etc.). It is worth mentioning that the usefulness of atopy patch tests used in the last 20 years for the diagnosis of food and aeroallergens allergies is very limited, because although they are specific, they are not sensitive. The latter holds true especially in children with gastrointestinal symptoms related to food allergy and, in the case of aeroallergens that could trigger AD, there is insufficient data(7,8).

Assessment of AD severity

In recent years, the objective assessment of the severity of AD has become especially important in the daily clinic, with the appearance of new treatments for severe AD and their high cost, as the fundamental criterion for deciding: first, its administration (limited to severe forms and with lack of response to classical treatments); and, subsequently, the continuity of its administration.

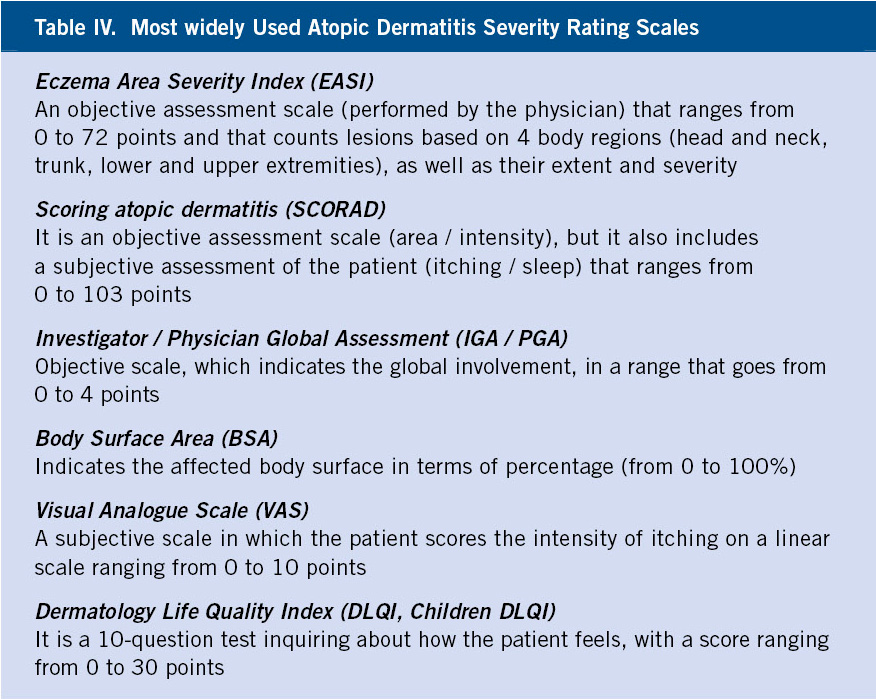

There are multiple assessment scales for the disease and quality of life, which were used primarily in research and which have now been transferred to routine clinical practice, although as we have already mentioned, only for patients with severe AD clinical pictures(9 ) (Table IV).

Approach / Treatment

In the management of AD, the treatment of the disease is as important or more as the prevention of the factors that trigger the flare-ups.

Recommendations include: avoiding triggers, making a regular use of emollient creams and treat flare-ups, so as to contain subclinical inflammation and symptomatic exacerbations(9,10).

Prevention

In preventing flare-ups, the education of children and parents, although time consuming, is particularly important. A study of an educational program for children, showed that 97% of those who received education on atopic dermatitis, obtained a significant decrease in SCORAD (Scoring Atopic Dermatitis) (Table IV) after 6 months(11).

In addition to educating on the characteristics and likely progress of the disease along with the basic measures to prevent flares, it must be taken into account that, in our society where “everyone” has an opinion, there are many things that are unproven and therefore must be avoided. For example:

• Only in patients with a proven food allergy, have exclusion diets proven certain degree of usefulness, although unable to fully control AD flare-ups. Only double-blind, placebo-controlled provocation tests are reliable. Allergy tests, RAST and prick tests, are positive in more than 40% of patients, without this involving clinical relevance. Epicutaneous tests to foods, which can be useful in patients with negative RAST and prick tests, although specific, they are not very sensitive.

It has been found that the exclusion of the most common allergens (cow’s milk, eggs, nuts, soy and fish) in high-risk children or in their mothers during pregnancy and lactation, decreases the prevalence of atopy during the first 2 years of life, although these differences are not sustained in the long term. These restrictive diets are very difficult to maintain overtime in children and can even turn out to be harmful (for instance, there is an increase in the frequency of allergy to peanut by delaying its introduction)(12). Some epidemiological studies have shown a significant association between food diversity given during the 1st year of life and protection against AD(13).

• Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended up to 4 months of age, as a method to prevent against food allergy associated with AD, but with a C level of evidence; that is, only one notch above experts´ opinion (D). Also, in children at high risk (first-degree relative with allergic symptoms), if breastfeeding is not possible, the use of hypoallergenic milk formulas is recommended; in this case, with a somewhat higher level of evidence (B)(9).

• Studies looking into the potential benefit of prebiotics and probiotics, remain currently inconclusive(14-16).

• Treatments not recommended by the doctor should be avoided (as they have not been proven to be effective or safe), such as: montelukast (leukotriene antagonist), topical capsaicin, essential fatty acids (topical or oral), phytotherapy (Chinese herbs), acupuncture, autologous blood, bioresonance, homeopathy, massage therapy or aromatherapy, salt baths and balneotherapy, vitamins and minerals, vitamin B12 in avocado oil, etc.(10).

• There is insufficient evidence to support that the use of non-sedating antihistamines reduces itching in patients with AD; however, they can be useful prior to exercise, because they reduce the itchiness caused by sweating. Similarly, sedative antihistamines, such as hydroxyzine, do not seem to control AD symptoms, however, by inducing sleep, they can improve rest and reduce scratching(17).

Healthy skin care is essential in these patients given the alterations in their skin barrier and increased transepidermal water loss, therefore: showers or baths should be brief (5 minutes) and with lukewarm water; bathing only 1-2 times a week is not a good idea, because it increases the skin proliferation of Staphylococcus Aureus; mildly irritating soaps should be used (oatmeal, oil soaps, etc.) and limited in extension (to surfaces that could be dirtier); the use of daily moisturizers or oil baths is essential; and the causes of itching and / or flare-ups must be avoided, such as the use of wool clothing directly on the skin as well as clothing or footwear that promote sweating, as well as exposure to clinically relevant allergens (diagnosed in allergy tests ).

When relapses are frequent, it is useful to apply calcineurin inhibitors or topical corticosteroids (two / three times a week) between flares, in the areas usually affected by atopic dermatitis. The usefulness of twice weekly bleach baths is more doubtful (various studies have shown no differences with water-only baths) and there are no references to the usefulness of nasal mupirocin in AD(18).

Treatment

Anti-inflammatory treatment is necessary, even in subclinical inflammation, in order to restore the balance in the inflamed skin as soon as possible.

Although eczema flare-ups tend to heal spontaneously within 1-2 weeks, all flare-ups need to be treated; because, if disregarded, they tend to become subintrant and spread out. Treatment must be adapted to the characteristics of the patient and the lesions they present and, hence, we will distinguish various situations with their corresponding treatment(19).

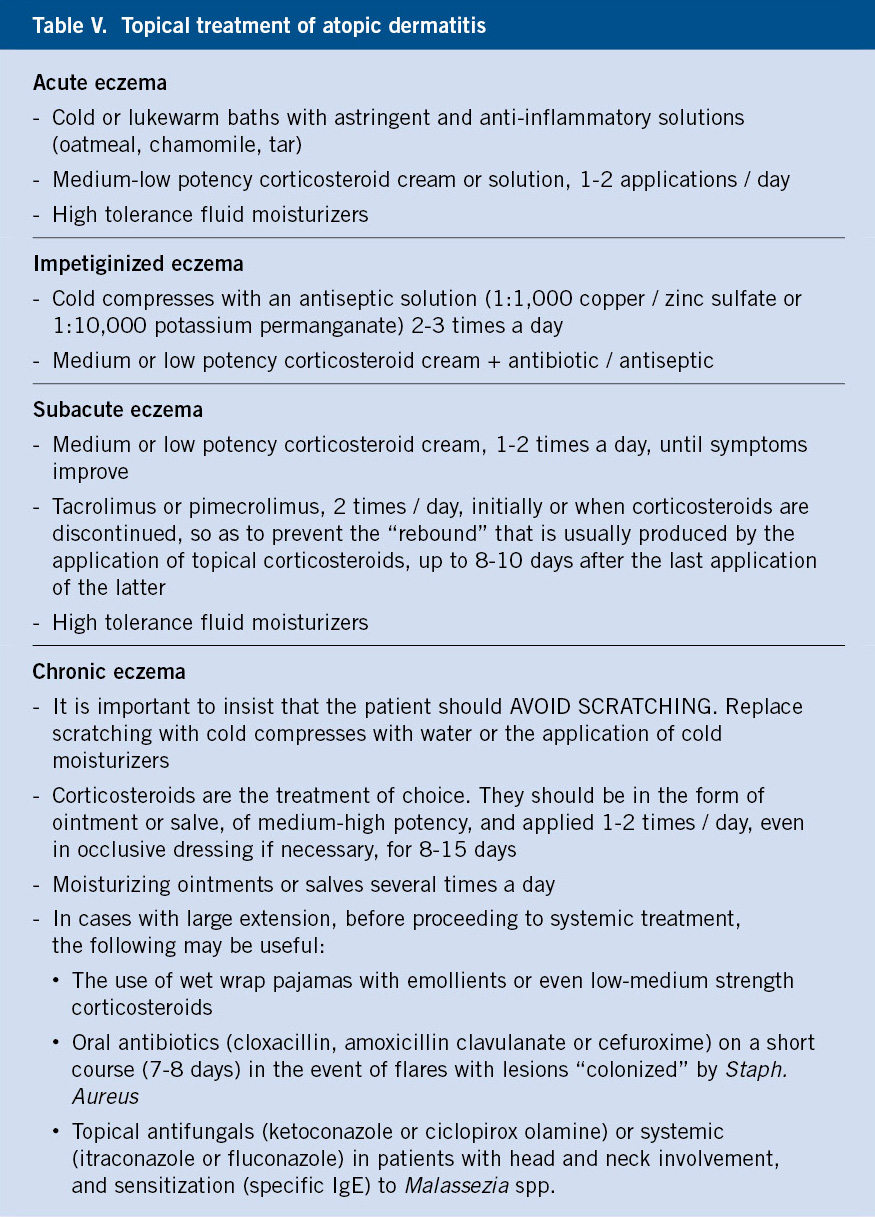

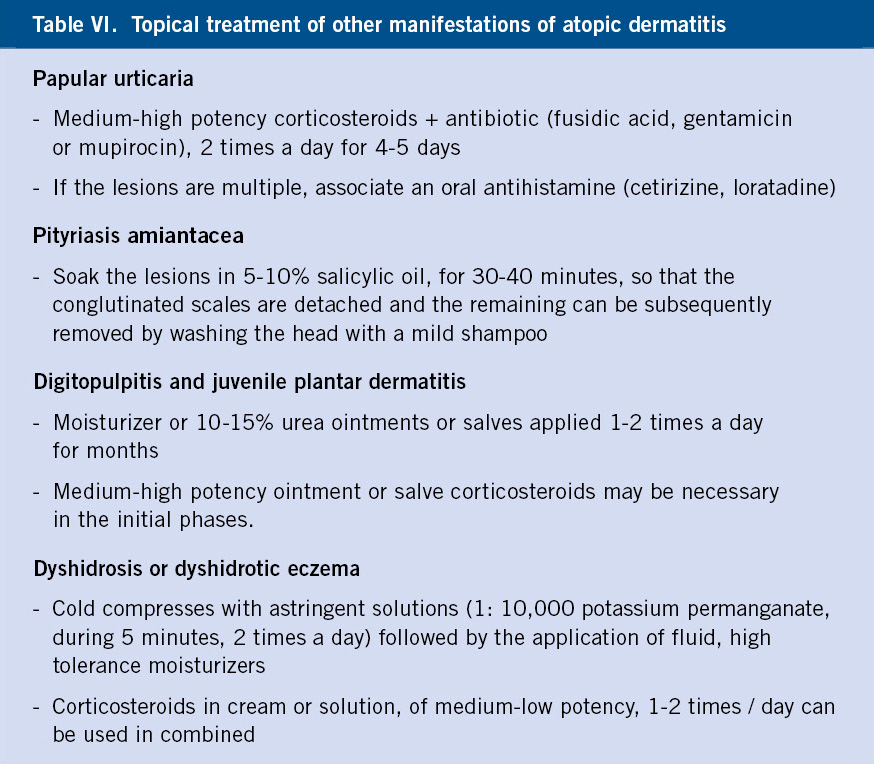

In mild forms (limited to 4 – 6 sites), anti-inflammatory treatment should be topical (Tables V and VI) and corticosteroids are the first choice, although calcineurin inhibitors are an option in case of subacute lesions.

In severe forms (with a significant extension or resistant to topical treatment, or with intense involvement of particularly important areas, such as the hands or face), it is necessary to maintain topical treatment and to add systemic treatment: oral corticosteroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil or phototherapy. Since January 31st, 2020, a biological drug, dupilumab, is also approved, initially only for children over 12 years of age, but from December 2nd, 2020 also for those over 6 years of age, which has shown results in children similar to those found in adults(20).

Microbial colonization of lesions and superinfection (Staphylococcus Aureus throughout the body and Malassezia furfur in head and neck lesions) seem to play a role in exacerbating flares and thus, justify the association of antimicrobials when these situations take place.

Treatments used

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line anti-inflammatory treatment in all phases of AD, but especially in the acute exacerbations. Except in chronic forms, where high-potency corticosteroids, such as clobetasol propionate are necessary, in the rest, low and medium-potency corticosteroids, such as clobetasone (low potency) or methylprednisolone aceponate (medium-high potency), usually suffice.

Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) are the alternative to topical corticosteroids and, more commonly nowadays, they are used in association to them so as to reduce their adverse effects. Tacrolimus 0.1% has an anti-inflammatory potency similar to that of a medium-potency corticosteroid and is clearly superior to pimecrolimus 1%.

Crisaborole 2% is an inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4, mainly 4B, which acts by reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as: TNF, IL12 and IL23. It has been approved for children over 2 years of age by the EMA (European Medicines Agency, March 27th, 2020), although it does not yet have the mandatory “therapeutic positioning report”. Its use is restricted to a maximum of 40% of the body surface and, until now, its superiority against topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors has not been demonstrated.

Other topical treatments that have demonstrated their usefulness, as adjuvants in the treatment of pruritus, are: doxepin (antihistamine), topical agonists of cannabinoid receptors, topical antagonists of l-opioid receptors or topical anesthetics, but they are NOT to be routinely recommended given their adverse effects, but also because its use is not approved for AD.

Systemic corticosteroids (at initial doses no greater than 0.5 mg/kg/day) produce rapid, albeit temporary, improvements with prompt relapses, which is why they should be used in acute exacerbations or when a quick response is required. “Corticophobia” is relatively frequent, both among doctors and patients, which requires pausing to explain the advantages and disadvantages of these drugs, as well as careful managing, clearly specifying the dose and duration.

Phototherapy (narrow band ultraviolet B and ultraviolet A1) is only authorized from 12 years old onwards, but it is very useful, although the need to travel and time schedule difficulties are an obstacle, sometimes insurmountable.

Cyclosporine is the only drug with authorized indication in Spain and the fastest acting one. Its efficacy is 53-95%, but this efficacy is limited by its medium and long-term side effects (fatigue, gingival hyperplasia, increased blood pressure, hypertrichosis, kidney failure, etc.).

Azathioprine or methotrexate, both of them used off-label in severe AD, are drugs with theoretically similar efficacy (26-39% and 42%, respectively), which are indicated in severe cases of AD. They are slow acting (it takes more than a month for improvement to be noticeable), but are generally well tolerated for months, although they require periodic analytical tests.

Other alternatives without approved indication for AD, are: mycophenolate mofetil, alitretinoin (for hand eczema), rituximab, omalizumab, ustekinumab, tofacitinib or apremilast, with scarce or variable response.

Targeted immunotherapy against specific allergens (dust mites or pollens) can be considered in sensitized patients with severe AD and a history of clinical exacerbations following exposure to these allergens.

Psychotherapy may be indicated in patients in whom exacerbations are related to episodes of stress (exams, relationship problems, etc.).

Dupilumab is a human monoclonal antibody that is administered subcutaneously. It blocks the alpha chain common to IL4 and IL13 and decreases not only the production of IgE, but also the inflammatory response mediated by Th2 cells. It is indicated in severe forms that do not respond to cyclosporine or that present some contraindication to its use. Dupilumab is the first in a series of new drugs, which are being released now for the treatment of moderate-severe AD. Some have already been approved by the EMA, such as baricitinib (which has the therapeutic positioning report of the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products pending), and others that have not yet been approved or are still in advanced stages of clinical trials, which will radically modify the prognosis of these patients.

Seborrheic dermatitis

Introduction

Seborrheic dermatitis is a common eczema, self-limited in childhood and with a chronic and relapsing course in adults.

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a common eczema, with two clinical forms, the one found in the infant and that of the adult. The first is self-limited to the first 3 months of life; while, the second is chronic and, although it can present in puberty, its frequency is highest during the fourth to sixth decades of life. The latter affects men more than women.

Etiopathogenesis

There is a relationship between seborrheic dermatitis and: overproduction of sebum (seborrhea), alterations in its composition and commensal yeasts of the genus Malassezia (Pityrosporum).

The etiopathogenesis is not fully known, but there is a relationship with: overproduction of sebum (seborrhea), alterations in its composition and commensal yeasts of the genus Malassezia (Pityrosporum). In babies, sebum is produced for a few weeks after birth, and the adult form of SD does not develop before puberty, supporting a role of androgens in the activation of the sebaceous glands. However, patients with SD may have normal sebum production, and those with excessive sebum production usually do not have SD. Malassezia Furfur and other species can be isolated from SD lesions, including infant SD, but there is no relationship between the number of yeasts and the severity of SD (unaffected skin may have a microorganism load similar to that of lesions). Anyhow, with antifungal treatment, skin lesions improve and the number of yeasts decreases and, these increase again when SD relapses. It has also been discovered that a major component of the resident skin microflora, Propionibacterium acnes, is greatly diminished in SD; thus, it could be associated with an imbalance of the microbial flora.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

The diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis is a clinical one. The lesions, generally not very bothersome, are located in areas with an abundance of sebaceous glands and, less frequently, in skinfolds.

The lesions consist of erythematous areas, generally well defined, with an unctuous sensation to the touch, and loose and moderate scaling. Vesiculation and crusting are rare to find. It is located in areas with an abundance of sebaceous glands (scalp, face, ears, presternal region) and, less frequently, in folds, but generalized and even erythrodermic forms can occur.

Seborrheic dermatitis of the infant

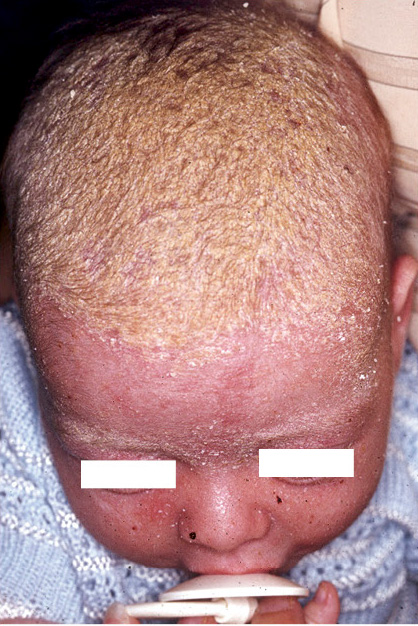

It usually begins a week after birth and can persist for several months. Initially, they are greasy scales, attached to the vertex and anterior fontanel, which can spread to the entire scalp (cradle cap) and face (Fig. 6).

Figura 6. Seborrheic dermatitis. Cradle cap.

Lesions in armpits, inguinal folds, neck, and retroauricular folds are usually more inflamed, although well defined. Lesions may become superinfected by Candida and, more rarely, by group A Streptococcus. A widespread rash of psoriasiform-appearing erythematous-scaly lesions may develop after an intensely inflammatory or superinfected SD, especially in the diaper area.

Seborrheic dermatitis in adults

In the scalp, the lesions are predominantly located in the parietal and vertex regions, but also in the occipital region, with a quite diffuse pattern. On the face, the lesions are located symmetrically in: nasogenial folds, eyebrows and retroauricular folds, but also in: the forehead, on the implantation edge of the scalp, in the glabella region and, occasionally, on the back of the neck, and also on the hairline. The lesions are not usually infiltrated and the scaling is fine and loose. Lesions on the trunk are located in the presternal area (in men) and in the center of the back where they tend to adopt a petaloid morphology. They are rarer in the armpits. Flare-ups lasting 1-2 weeks are more or less recurrent and they are frequently related to stress. Pruritus is usually moderate, but may be severe, and folliculitis (Pityrosporum) and inflammation of the meibomian glands in the palpebral tarsus (meibomitis) may be seen.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis is with atopic dermatitis.

Infantile SD differs from atopic dermatitis by: its earlier onset, the different distribution pattern and the absence of itching, irritability and insomnia. Irritant diaper rash is limited to the diaper area and usually does not affect the folds. Yeast (Candida) diaper rash preferentially affects the folds, with occasional fissuring, and satellite lesions are usually present around the main lesions. In inverted psoriasis of the diaper area, the lesions are more infiltrated and demarcated, and the presence of typical lesions in other locations aids in the diagnosis.

Pityriasis amiantacea (thick asbestos-like flakes which adhere to strands of hair on the scalp, in an irregular shape) which could be confused with cradle cap, occurs in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.

Other rare disorders, which must also be considered in the differential diagnosis, especially in treatment-resistant forms, are: Langerhans cell histiocytosis, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and Leiner’s disease. The latter, previously considered the maximal expression variant of infantile SD, is now considered erythroderma in the context of underlying immunosuppression.

Another differential diagnosis, to be considered especially in prepubertal children, and primarily in black ethnicity, with scaling of the scalp, is tinea capitis (due to Trichophyton tonsurans).

When SD is extensive and severe in adults, HIV infection should be ruled out. The main differential diagnosis is with psoriasis of the scalp. In this case, the lesions are erythematous plaques covered by whiter and adherent scales, especially in the occipital and temporal regions.

Pityriasis simplex (dandruff) is defined as a diffuse, more or less intense, flaking of the scalp and beard, but without significant erythema or irritation. This common disorder can be considered the mildest form of seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp.

Treatment

Washing the lesions with a 2% ketoconazole shampoo and the application of an emollient cream suffice in most cases.

Both, infantile and adult forms of SD satisfactorily respond to washing with mild shampoos and application of emollients. Ketoconazole (2%) or ciclopirox olamine cream or shampoo is indicated in more extensive or persistent cases. In acute phases, short courses of low-potency topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors (although not approved for this indication) can be used to suppress inflammation.

The role of the Primary Care pediatrician

The role of the Primary Care pediatrician is to recognize the typical and less typical forms of both diseases, in order to be able to treat mild or moderate forms, and refer the most serious forms or those that do not respond to treatment to the specialist. In the case of AD, he plays a fundamental role in the prevention of flare-ups, in the education of patients and their families (it should not be forgotten that it is often a familial disease) as well as in screening for other diseases associated with AD (asthma, environmental allergy, etc.).

Bibliography

The asterisks show the interest of the article in the opinion of the authors.

1.** Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 1.Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70: 338-51.

2.* Spergel JM. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis and atopic march in children. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2010; 30: 269-80.

3.* Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Sánchez L, Sastre J. Prevalence of Severe Atopic Dermatitis in Adults in 3 Areas of Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2018; 28: 195-97.

4.* Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Carrascosa Carrillo JM. Impacto económico de la dermatitis atópica en adultos: estudio de base poblacional (estudio IDEA). Actas Dermo-sifiliográficas. 2018; 109: 35-46.

5.** Patrick GJ, Archer NK, Miller LS. Which Way Do We Go? Complex Interactions in Atopic Dermatitis Pathogenesis. J Investig Dermatol. 2021; 14: 274-84.

6. ** Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1980; 92: 44-7.

7. * Luo Y, Zhang GQ, Li ZY. The diagnostic value of APT (atopy patch test) for food allergy in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2019; 30: 451-61.

8. * Dickel H, Kuhlmann L, Bauer A, Bircher AJ, Breuer K, Fuchs T. Atopy patch testing with aeroallergens in a large clinical population of dermatitis patients in Germany and Switzerland, 2000-2015: a retrospective multicentre study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020; 34: 2086-95.

9. *** Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2018; 32: 657-82.

10. *** Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018; 32: 850-78.

11.** Heratizadeh A, Werfel T, Wollenberg A, Abraham S, Sybylle PH, Schnopp C, et al. Effects of structured patient education in adult atopic dermatitis: Multi-center randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017; 140: 845-53.

12. * Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy.N Eng J Med. 2015; 372: 803-13.

13. ** Roduit C, Frei R, Loss G, Büchele G, Weber J, Depner M, et al. Development of atopic dermatitis according to age of onset and association with early-life exposures. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 130: 1306e5.

14. * Fölster-Holst R, Müller F, Schnopp N, Abeck D, Kreiselmaier I, Lentz T, et al. Prospective, randomized controlled trial on Lactobacillus rhamnosus in infants with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.Br J Dermatol. 2006; 155: 1256-61.

15.* Rosenfeldt V, Benfeldt E, Nielsen SD, Michaelsen KF, Jepessen DL, Valerius NH, et al. Effect of probiotic Lactobacillus strains in children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 111: 389-95.

16. * Grüber C. Probiotics and prebiotics in allergy prevention and treatment: future prospects. Exp Rev Clin Immunol.2012; 8: 17-9.

17. ** He A, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB. An assessment of the use of antihistamines in the management of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018: 79: 92-6.

18. ** Hon KL, Tsang YCK, Lee VWY, Pong NH, Ha G, Lee ST, et al. Efficacy of sodium hypochlorite (bleach) baths to reduce Staphylococcus aureus colonization in childhood onset moderate-to-severe eczema: A randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016; 27: 156-62.

19. *** Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Vekeman F, Gadkari A, Kaur M, Mallya UG, et al. Treatment patterns of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: A claims data analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol.2020; 82: 651-60.

20.** Igelman S, Kurta AO, Sheikh U, McWilliams A, Armbrecht E, Jackson Cullison SR, et al. Off-label use of dupilumab for pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: A multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82: 407-11.

21. Prieto-Torres L, Torrelo A. Dermatitis atópica y otras erupciones eccematosas. Pediatr Integral. 2016; XX(4): 216-26.

Recommended bibliography

- Patrick GJ, Archer NK, Miller LS. Which Way Do We Go? Complex Interactions in Atopic Dermatitis Pathogenesis. J Investig Dermatol. 2021; 14: 274-84.

It summarizes the current knowledge on the etiopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2018; 32: 657-82.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018; 32: 850-78.

They both reflect the current European consensus in the treatment of atopic dermatitis.

- Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Vekeman F, Gadkari A, Kaur M, Mallya UG, et al. Treatment patterns of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: A claims data analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82: 651-60.

It highlights how things are currently being done and what has to be improved.

| Clinical case |

|

11-year-old patient who has noticed for months, the appearance of cracks in the 1st and 2nd toes of both feet. The examination is shown in figure 7.

Figure 7. |

Atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis